By Marshall Croddy

When Constitutional Rights Foundation incorporated in 1962, the world was a very different place. . .

Riots broke out as James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi.

In the case of Engel v. Vitale, the U.S. Supreme Court banned mandatory prayers in public schools causing widespread protests.

The Cold War peaked in October with the Cuban Missile Crisis.

|

| Vivian Monroe |

In 1962, a small, relatively inactive Los Angeles non-profit organization took on new life when it raised an $11,000 annual budget and hired an employee at $50 per week. The employee’s name was Vivian Monroe.

While Monroe set about the task of raising money for the struggling organization, other forces were at work that would shape its future. A New York organization, the Civil Liberties Educational Foundation (CLEF), sponsored a workshop at Williams College in Massachusetts for the purpose of improving the teaching of the Bill of Rights. Attended by master teachers from throughout the country, the meeting produced a call to action, citing the lack of systematic study of the Bill of Rights in the nation’s schools. These findings later served as a basis of a report presented to the National Council of the Social Studies and were linked to an address by United States Supreme Court Justice William Brennan at an annual meeting. A germinal conference for prominent educational, legal, and media leadership at Airlie House, Virginia, followed, chaired by Justices Douglas and Brennan and led by Telford Taylor, counsel at the Nuremberg Trials. The seeds for improved teaching about the Bill of Rights, and indeed the whole field of law-related education, had been sown.

The Los Angeles Civil Liberties Foundation sent two representatives to the Airlie Conference: Deans Richard Maxwell of the UCLA Law School and Howard Wilson of UCLA’s School of Education. Both came back with great purpose and enthusiasm. They suggested that the foundation organize a California workshop for secondary teachers and administrators to develop materials and methods for teaching the Bill of Rights. As a result of this, a conference was held in Santa Barbara, and a number of in-service programs were established in the school communities represented by the participants.

Although the workshop was successful, it soon became apparent that a more systematic and broad-based effort would be needed to improve education about the Bill of Rights in California. The foundation approached the California State Board of Education with the assistance of Associate Superintendent Richard Clowes and the support of board member William Norris, now a retired U.S. federal judge, to ask that a policy be established on teaching the Bill of Rights. The board responded positively and asked one of its members, Methodist Bishop Gerald Kennedy, to form a Bill of Rights committee to make recommendations. In turn, the committee requested that the California State Department of Education conduct a study to determine how the subject was treated in the curriculum guides and textbooks in use at the time. Although informal, the study concluded that the Bill of Rights was generally treated textually with little or no focus on contemporary issues or modem applications.

On the basis of this study, the State Board adopted a policy statement, dated October 10, 1963 that read in part:

[T]he study of the Bill of Rights is of greatest importance and we believe that more attention should be given to the Constitution of the United States.

The situation in some communities indicates that too many Americans have never understood the Bill of Rights, and the present civil rights crisis reveals how sketchy has been our education in this field. Young Americans facing communist indoctrination pressure ought to be able to counter with an affirmation of their democratic faith. We believe that one of the essential things we must now do is to establish in our children the American belief in the dignity and rights of every person.

The situation in some communities indicates that too many Americans have never understood the Bill of Rights, and the present civil rights crisis reveals how sketchy has been our education in this field. Young Americans facing communist indoctrination pressure ought to be able to counter with an affirmation of their democratic faith. We believe that one of the essential things we must now do is to establish in our children the American belief in the dignity and rights of every person.

Viewed from the perspective of today, it might seem odd that a rationale for improved Bill of Rights education would contain as a key element the need to arm students against “communist indoctrination pressure.” One must recall the climate of the times. Echoes of McCarthyism still reverberated, and the Cuban Missile Crisis had erupted only one year earlier, renewing fears of Soviet aggression.

In addition to issuing the policy statement, the State Board of Education also created a Bill of Rights Advisory Panel of 15 members and named Dean Maxwell as its chair. With this panel in place, the groundwork had been completed for state-wide development of pre-service and in-service teacher training, teacher weekend conferences, and student and teacher contests, activities that would occupy the organization for many years.

The year 1963 ended with the organization changing its name to Constitutional Rights Foundation (CRF) (Certificate of Amendment 1963). From then on, its mission would be education rather than legal advocacy.

The First Materials

In 1964, through the efforts of Vivian Monroe, Constitutional Rights Foundation raised $30,000 from private sources to fund a grant to the State Department of Education to implement the state board’s policy. But before the program could start, Dean Maxwell and Thomas Brandon, president of the State Board had to fight back objections posed by Dr. Max Rafferty, the superintendent of public instruction, who opposed the role of the foundation on ideological grounds.

Considered top priority was the development of materials that would better prepare teachers to educate their students about the essential doctrines of the Bill of Rights, the germinal cases of the U.S. Supreme Court, and current issues and trends. The material was deemed critical because most textbooks of the time treated the Bill of Rights only in the historic sense or as a part of the structures and institutions of government (Todd Clark interview, 1991). In addition, the foundation had concluded, based on teacher comments, that many teachers were reluctant to cover the subject because they felt uncomfortable with their own knowledge about it.

To create the proposed materials, the foundation assembled a team representing the fields of law and education. This formula foreshadowed the approach that would be taken in many future CRF publications. The team included William Cohen, professor of law at UCLA; Murray L. Schwartz, also a professor of law at UCLA; and DeAnne Sobul, curriculum consultant, Los Angeles Unified School District.

The materials were completed in 1966 under the title of The Bill of Rights—A Source Book for Teachers. Published with a press run of 1,500 in a 8.5" x 11" format, the blue-covered volumes provided teachers with a thematic background to the major doctrines of the Bill of Rights, supported by case materials. While pedagogically limited, the books nevertheless gave educators in California a systematic background for teaching about contemporary issues of the Bill of Rights.

A Focus on Teaching

In 1967, Vivian Monroe hired Todd Clark, a social studies teacher from Azusa High School, to introduce The Bill of Rights—A Source Book to teachers. His first task was to organize and staff implementation meetings throughout Southern California. While CRF covered the Southland, the State Department of Education, guided by the Bill of Rights Advisory Panel, and supported by federal ESEA Title V Funds, conducted a series of 18 summer workshops at California state colleges for teachers (Survey of CRF 1970).

Clark recruited prospects to attend the statewide, intensive training conferences held at the Carmel Valley Inn in Monterey County. Conducted for some 325 master teachers and administrators, representing nearly 100 school districts, between the years 1968 and 1971, the workshops used the Source Book, but also concentrated on methodological concerns (CRF Document, 1971). Presenters included Fred Newman and Howard Mellinger, and the participants’ list formed the basis of what would become CRF’s statewide contact network in the years to come.

Clark recruited prospects to attend the statewide, intensive training conferences held at the Carmel Valley Inn in Monterey County. Conducted for some 325 master teachers and administrators, representing nearly 100 school districts, between the years 1968 and 1971, the workshops used the Source Book, but also concentrated on methodological concerns (CRF Document, 1971). Presenters included Fred Newman and Howard Mellinger, and the participants’ list formed the basis of what would become CRF’s statewide contact network in the years to come.

Teachers always have played a key role in CRF’s success. Mock Trial and History Day teacher sponsors have spent countless hours preparing students to compete; teachers help us design and field test innovative programs; classroom teachers participate in CRF professional development sessions and come away ready to utilize what they learn with their students; and teachers select and use our curricula and publications. Through them, we have made a difference in the education of millions of students.

Bill of Rights in Action

Bill of Rights in Action

First published in early 1967, the newsletter was originally conceived as a biannual information piece for teachers. It contained a potpourri of articles, book reviews, program notes, and lesson plans and was distributed free-of-charge to a few hundred teachers statewide. By 1972, the newsletter had become a subscription publication with some 400 California teachers receiving it four times during the school year.

In the mid-1980s, educational changes and economic realities caught up with the nearly 20-year-old publication. Reflecting tightening school budgets and a national trend away from subscription classroom materials, subscribers steadily declined from 1979 through 1983. Ultimately, and to the credit of CRF’s Board of Directors, the dilemma was resolved in favor of student impact rather than cost. With the strong support of Jerome Byrne, the chair of the CRF board Publications Committee, the staff proposed that Bill of Rights in Action be reduced to an eight-page format and distributed free-of-charge to educators throughout the United States. The board agreed and approved a press and mailing run depending on demand. In the winter of 1984, the first Bill of Rights in Action in the new format was produced and mailed. With longtime contributor Carlton Marts, CRF staff write and edit BRIA. Today, each issue reaches some 40,000 educators and hundreds of thousands of students in all 50 states.

Governance

|

|

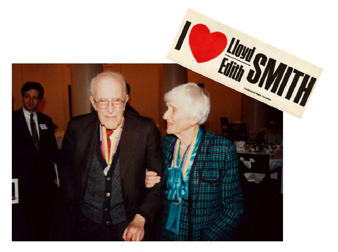

Lloyd and Edith Smith

|

CRF has always been fortunate in the quality and dedication of its Board of Directors. Even from its early days, CRF had a board of very prominent individuals. Early members included Joseph Ball, Bayard Berman, Jerry Bryne, Gene Kaplan, Burt Lancaster, Dean Richard Maxwell, William Norris, Dr. Julian Nava, Richard Rogan, Paul Shrade, Marvin Sears, Lloyd Smith, Clore Warne, and Robert Wise. Many of these members made great contributions and served for many years. For example, long-serving member Lloyd Smith’s generosity kept the struggling organization financially afloat, and Marvin Sears became CRF’s longest serving board member and continues to be active in emeritus status.

As the organization grew, so did the size of the board. By the 1970s and 1980s, CRF board members represented many major law firms, corporations, and the bench. Among the prominent members of this era were: Judge Wm. Matthew Byrne, Stuart Buchhalter, Robert Carlson, Judge Judith Chirlin, Justice James Cobey, Judge Ronald George (soon to become Chief Justice of California), Norman Clement, Louis Colen, Russsel Freeman, Dr. Harry Handler, Alan Jonas, Norman Lear, Sol Marcus, Judge Chritopher Markey, Jr., Jess Marlow, Charles Manatt, Burt Pines, Richard Richards, Charles Rickerhauser, Robert Rosensteil, Alan Rothenberg, Edward Rubin, Judge Pamela Ryder (later a judge on U.S. 9th Circuit), Gene Shutler, Sanford Sigoloff, Eve Slaff, Dr, Graham Sullivan, and Justice Arleigh Woods.

|

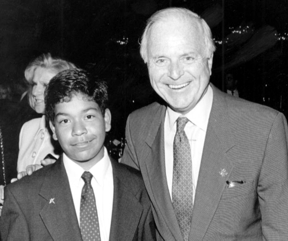

| T. Warren Jackson CRF Board Chair |

In the 1990s, a new leadership emerged. Robert Aronoff, Helen Berstein, Ron Beard, William Bogaard (soon to become Mayor of Pasadena), John Cooke, Knox Cologne, Jerry Chaleff, Jim DeMeules, Lee Edmon, Alan Friedman, Haley Fromholz, Robert Henigson, Harry Hufford, Rick Kolodny, David Laufer, Leslie Lo Bough, Stephen Meier, Christopher Paskach, Tom Pfister, Patrick Rogan, Peggy Saferstein, Marjorie Steinberg, Susan Troy, and Harry Usher.

In the first decade of the new millennium, the tradition continued with Jane Arnault, Joseph Calabrese, Jerome Coben, Nestor Barrero, Louis Eatman, Joel Feuer, Robert Greenfield, T. Warren Jackson, Judge John Kronstadt, Michael Lawson, Scott Lichtig, Diane Ogilvie, Sharon Matsumoto, Louis Meisinger, Thomas Phelps, W. Davis Smith, Gregory Stone, Robert Stern, Lois Thompson, Gail Migdal Title, and Carton Varner.

Spring Dinner

CRF’s annual fundraising dinner, now a Los Angeles tradition, evolved from a Law Day event for teachers. Over the years, it became a must-attend dinner for the Los Angeles legal elite, benefactors, and government leaders. Growing in stature, the dinner has hosted up to 1,000 guests at various premier hotels—the Downtown Biltmore, the Beverly Wilshire, the Beverly Hilton, and the Century Plaza.

|

| A student with Hon. Richard Riordan, former Mayor of Los Angeles. |

Prominent and inspirational speakers have always been among the highlights of the evening. Drawn from the fields of government, law, letters, and journalism, speakers have included Vice-President Al Gore; U.S. Supreme Court Justices William Brennan, Abe Fortas, and Antonin Scalia; Rudolf Giuliani; Chief Justice of California Malcom Lucas; Senators George McGovern and Birch Bayh; Governor of Kansas Kathleen Sebelius; Chief of Police William Bratton; Walter Dellinger; Alan Dershowitz; Erwin Chemerinksy; Kathleen Sullivan; Michael Crichton; Michael Beschloss; David Halberstam; Doris Kerns Goodwin; Frank McCourt; David McCullough; Tom Brokaw; Art Buchwald; Jack Nelson; Andy Rooney; and Mike Wallace. (CRF Document, Past Honorees and Speakers, 2011)

Another dinner highlight is the Bill of Rights Award bestowed on honorees who have made a significant civic contribution. They include Dr. Ronald Sugar, Northrop Grumman; Thomas Mars, Walmart USA; Peter Ligouri, Fox Broadcasting; Dian Ogilvie, Toyota Motor Sales; John Bryson, Edison International; Dr. Dale Laurance, Occidental Petroleum; Louis Meisinger, The Walt Disney Company; Hon. Richard Riordan, Mayor of Los Angeles; Jack Valenti, Motion Picture Association of America; Raymond Fisher, Heller, Erhman, White, & McAuliffe; John Cooke, The Walt Disney Company; Richard Stegemeier, Unocal Corporation; Alan Rothenberg, President California Bar Association; Robert Erburu, Times Mirror; Rocco Siciliano, TICOR; Franklin Murphy, Los Angeles Times.

CRF Goes Nationwide

|

|

Carolyn Pereira, |

The development of the national law-related education movement during the 1970s presented new opportunities and challenges for CRF. Spurred by the “new social studies” trends, the movement trained thousands of teachers in legal content and interactive methodology and established many new courses in schools. It also created an expanded demand for supplementary materials to support these efforts. The emphasis of the movement was on practical law and criminal justice. CRF had pioneered such programs with Youth and the Administration of Justice (YAJ), first in the Southern California region, and then statewide with the support of the California Office of Criminal Justice Planning. To support these programs, CRF developed materials that were eventually published as a text by Scholastic, Inc., in 1978. Called Criminal Justice, the book, provided an overview of criminal law, the role of the police, the function of courts, and the corrections system. A companion book, Civil Justice, took a similar approach to the civil law system.

With growing prominence in Los Angeles and California, CRF moved to establish a presence in different areas of the country. CRF offices or affiliates were established in San Francisco, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Chicago in the early 1970s and in Orange County in the 1980s. Led by educator Carolyn Pereira, CRF/Chicago became a strong national partner with CRF. Though it eventually became its own independent non-profit, CRF/Chicago collaborates with CRF on educational programs and national outreach efforts even today. Orange County also evolved into a separate entity, but continues to deliver strong programming throughout its region.

In 1978, joining five national partners—the American Bar Association, Constitutional Rights Foundation/Chicago, Law in a Free Society (now the Center for Civic Education), Pi Alpha Delta (the national legal fraternity), and Street Law—CRF received funding for national dissemination of law-related education funded by the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. The partnership conducted hundreds of teacher conferences and professional development sessions over the years and continued until 2005.

Volunteers

Early on, CRF promoted and developed programs to encourage volunteer attorneys, business professionals, and government officials to become part the educational process by working with teachers and students to provide a real-life perspective and expertise to the subjects being studied in the classroom. Volunteers also served as role models and inspiration for students who otherwise might not have aspirations for or connections to professional careers. Later research conducted on CRF programs demonstrated that such volunteer experiences can have a powerful impact on young people. Over the years, thousands of lawyers, judges, police officers, business people, and governmental representatives have devoted countless hours to our educational programs.

In Los Angeles, CRF developed a very successful student conference to commemorate Law Day each May. Local teachers from around Southern California brought their students to the Los Angeles Courthouse for a day of workshops and other learning experiences. Volunteer attorneys and participating agencies such as LAPD, the County Coroner, and the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office conducted the workshops on a range of legal topics. At its height, Law Day involved well over 1,000 students and featured a keynote, lunch, student entertainment, and bus service to and from the event.

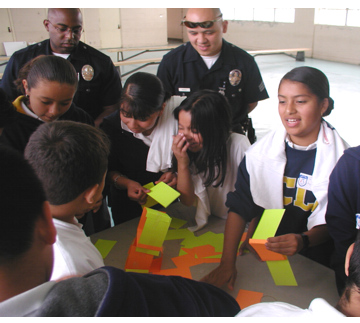

Cops and Kids, based on CRF’s successful Police Patrol classroom simulation, also developed at this time. The program brought students and police officers together to learn about police procedures and due process and to improve attitudes between youth and police. In the simulation, students take the role of police officers to handle realistic law-enforcement situations coached and debriefed by real officers. In the 1990s, CRF expanded the program conducting numerous school-wide and region-wide conferences at the Los Angeles Convention Center involving up to 1,200 students from around the city and 120 LAPD and LAUSD police officers. A national version of the program was conducted around the country in the early 2000s for school resource officers. Evaluations consistently show positive gains in both student and police attitudes about one another as a result of the program.

Cops and Kids, based on CRF’s successful Police Patrol classroom simulation, also developed at this time. The program brought students and police officers together to learn about police procedures and due process and to improve attitudes between youth and police. In the simulation, students take the role of police officers to handle realistic law-enforcement situations coached and debriefed by real officers. In the 1990s, CRF expanded the program conducting numerous school-wide and region-wide conferences at the Los Angeles Convention Center involving up to 1,200 students from around the city and 120 LAPD and LAUSD police officers. A national version of the program was conducted around the country in the early 2000s for school resource officers. Evaluations consistently show positive gains in both student and police attitudes about one another as a result of the program.

Lawyer in the Classroom was another innovation. Volunteer attorneys with the support of staff developed lessons on a range of legal topics and visited classrooms to help teachers present the materials. The essence of this program continues today in two forms—Courtroom to Classroom, in which volunteer judges and attorneys visit area classrooms to make a PowerPoint presentation on Constitutional issues and conduct a moot court, and the Appellate Court Experience, a collaboration between CRF and the California Court of Appeal 2nd District that involves attorney classroom visits, students attending an actual appeal hearing and interacting with the justices, and a follow-up moot court.

Lawyer in the Classroom inspired the creation of Business in the Classroom, sponsored by local business entities including Bank of America, Standard Brands Paint Company, ARCO, Security Pacific Bank, and Arthur Anderson and Co. Volunteers helped create lessons relating to business law and ethics and delivered them to classrooms. The program also sponsored an annual Business in the Classroom student conference for local schools.

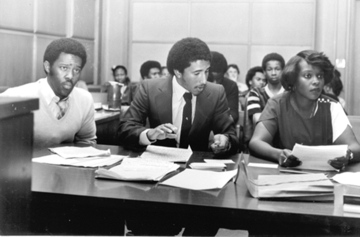

In 1978, CRF launched its Mock Trial Competition, in which schools form teams and compete against other schools in a simulated criminal trial in real courtrooms before real judges and attorney scorers. Students take the roles of prosecuting and defense attorneys, witnesses, bailiffs, and timekeepers. Beginning with a small competition in Los Angeles with teams from four local high schools, the program was expanded to other California counties with the help of Judge William Hogoboom, then the presiding judge of Los Angeles County Courts. CRF began conducting an annual State Finals to which each participating county sent its winning team. For over 30 years, CRF staff assisted by law school interns has developed the case materials for each competition, materials that are often adapted by other states for their own programs. Each year, the California Mock Trial involves teams from up to 36 California counties, nearly 10,000 students, and hundreds of teacher and legal volunteers.

In 1978, CRF launched its Mock Trial Competition, in which schools form teams and compete against other schools in a simulated criminal trial in real courtrooms before real judges and attorney scorers. Students take the roles of prosecuting and defense attorneys, witnesses, bailiffs, and timekeepers. Beginning with a small competition in Los Angeles with teams from four local high schools, the program was expanded to other California counties with the help of Judge William Hogoboom, then the presiding judge of Los Angeles County Courts. CRF began conducting an annual State Finals to which each participating county sent its winning team. For over 30 years, CRF staff assisted by law school interns has developed the case materials for each competition, materials that are often adapted by other states for their own programs. Each year, the California Mock Trial involves teams from up to 36 California counties, nearly 10,000 students, and hundreds of teacher and legal volunteers.

CRF’s local law and business programs were supported by active advisory groups. The Lawyers Advisory Council consisted of leading lights of the Los Angeles legal community including Francis Wheat, Candace Cohen, Anne Lloyd Crotty, John Emerson, Larry Feldman, Daniel Fogel, Fulton Haight, Lawrence Irell, Leon Kaplan, Richard Neal, Frank Rothman, John V. Tunney, Evelle J. Younger, and Paul Ziffren.

The Business Advisory Committee representing prominent members of the corporate community included Robert Erburu, James Galbraith, Walter Gerken, Joseph Kresse, James Miscoll, Robert Parsons, Clare Peck, Ray Remy, Rodney Rood, Togo Tanaka, James Ukropina, and Franklin Ulf.

CRF Publications

Marshall Croddy, an attorney and curriculum writer, joined CRF in 1979 and became CRF’s director of publications in 1983. He built an extensive catalog of publications known throughout the country for their accurate and interesting content, balance, and innovative methodologies, and developed the Foundation’s capacity to produce sophisticated private and governmental grant proposals. Later, he became a recognized leader in the fields of law-related and civic education and developed numerous programs of national significance.

The decade of the 1980s presented new challenges to the foundation. Trends toward a mandated curriculum, stretched school budgets, greater teacher accountability, and standardized assessment required more creativity in finding ways to get education about law and the Bill of Rights into the school curriculum.

The decade of the 1980s presented new challenges to the foundation. Trends toward a mandated curriculum, stretched school budgets, greater teacher accountability, and standardized assessment required more creativity in finding ways to get education about law and the Bill of Rights into the school curriculum.

To meet these demands, CRF, in 1982, began to develop what might be called an infusion strategy. The process began by asking the not-too-original, but simple, question, “How can we make education about law and the Bill of Rights fit into what teachers are already teaching?” After an extensive survey of curriculum guidelines throughout the United States, CRF noted that certain core social studies courses still dominated social studies. They were U.S. history, U.S. government, world history, and, to a lesser degree, economics and problems and issues courses. Based on this information, CRF began to develop materials that would place a law-related and constitutional content overlay into an established course linked to the sequence or thematic organization of major textbooks. It was also deemed important that the materials offer enrichment to the subject being taught, so that even traditional teachers might be attracted to their use.

At about the same time, CRF began to produce curriculum and market publications using this model. Today, CRF offers some 40 titles covering educational standards in civics, law, government, and history for classrooms ranging from the 3rd grade to the 12th grade, including Criminal Justice in America, now in its fifth edition. Over the years, CRF publications have been used by hundreds of thousands of students and raised over $2 million dollars in revenue that has been used to support the publications program.

In 1983, the newly formatted Bill of Rights in Action was also organized to give teachers from a variety of subject areas lessons to use in their specific courses. Still organized around a particular theme, the lessons themselves treat the theme in the context of the subject being taught.

CRF Gets a Home

Through its first two decades, CRF was housed in a variety of donated and rental offices from downtown to the Westside of Los Angeles. In 1983, with growing support and staff, the Board of Directors began a capital campaign to acquire a permanent home for the foundation. Led by chair Jack Stutman, the campaign raised $1.15 million, and with the help of board member Alan K. Jonas, identified a building in the Wilshire Center area of Los Angeles. Located midway between Downtown and Century City, this was an ideal location for reaching out to schools. Major donors to the effort included the W.M. Keck Foundation, City of Los Angeles, Edith and Lloyd Smith, and the Weingart Foundation. With the campaign a success, the foundation moved to its newly renovated offices at 601 South Kingsley Blvd in 1984.

Insuring the Future

At the suggestion of board members and after the building was purchased, CRF began planning for its future. In 1990, CRF established its first endowment in the name of Alan I. Rothenberg, a former president. Others followed in the names of prominent CRF board members and benefactors. They include the Jerome Byrne Endowment, James A. Cobey Endowment, CRF Endowment, Creative Kids Endowment, Robert & Phyllis Henigson Endowment, and Jack Stutman Endowment.

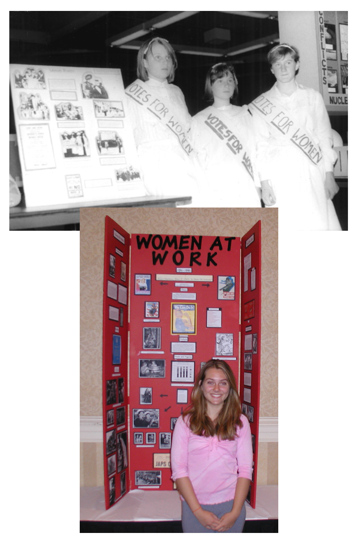

History Day

From 1985 through 2010, CRF organized and conducted History Day in California, one of the largest and most successful History Day programs in the United States. Like a science fair with history as the subject, History Day attracted thousands of students from up to 34 California counties to research and develop projects in various categories including papers, performance, exhibit, and documentary. Projects were rigorously judged by panels of experts. Once each year, student county winners from the state finals competed at the State Finals involving 1,000 students and their families. A state leader, CRF developed two new categories for competition—the poster competition for elementary students and the website category for those technologically inclined.

Sports and the Law

Sports and the Law was another effort to provide teachers and students with highly motivating programs and educational materials. A program curriculum using the metaphors of sport—rules, referees, sportsmanship—was adopted from a St. Louis effort to teach young people about law, the legal system, and citizenship. Sports and Law attracted an enthusiastic group of lawyers who visited classrooms and organized events to support the program. The program also hosted sport and academic competitions and conferences for students from many local urban schools. An annual fundraising dinner featured sports celebrities such as John Wooden, Tommy Lasorda, Kareem Abdul Jabar, and Al Davis and pro team sponsors including the L.A. Dodgers, Lakers, Clippers, Rams, and Raiders. Its advisory group included Dr. Anthony Daly, Marvin Demoff, Dr. Philip Fagan, Margaret Farnum, John Fricks, Irv Kaze, Robert McCarthy, Ron Orr, Fred Rosen, George Short, Ted Steinberg, Gil Stratten, Amy Trask, Jane Usher, Terdema Urssery, and Jerry West.

The Bicentennial Era

The Bicentennial Era

The five-year bicentennial period, beginning with the 1987 commemoration of the U.S. Constitution and leading to the Bill of Rights commemoration in 1991, provided CRF with new opportunities. With the 1987 commemoration, CRF began a collaboration with the Huntington Library, utilizing its rich archival resources to publish a documentary history of the Constitution called Letters of Liberty. Then, collaborating with the Los Angeles County Bar Association, CRF wrote a series of “bicentennial minutes” narrated by Gregory Peck that aired on radio stations throughout the year.

For the bicentennial of the Bill of Rights, CRF organized a Southern California–wide educational celebration. Led by former president Raymond C. Fisher, now a 9th Circuit federal appellate judge, and sponsored by major corporations, including Times Mirror, Unocal, and Southern California Edison, and a range of local foundations, the celebration provided programming and events for local schools, libraries, and civic groups. A Bill of Rights on Wheels travelled around the region bringing learning experiences to elementary students, Bill of Rights banners festooned the airport and major thoroughfares, and CRF published and distributed a second documentary history in collaboration with the Huntington called Foundations of Freedom.

The year-long celebration culminated with gala dinner on the grounds of the Huntington Library and Gardens featuring a keynote address by former President Jimmy Carter and with a city celebration of Bill of Rights Day held on the steps of the Los Angeles City Hall. A 50-foot-tall banner with the logo of the celebration draped the south wing; bands, choirs, and celebrity speakers including Ed Asner, Christian Slater, and Shelly Duvall made presentations; and a sculpture was dedicated for a time capsule on the City Hall grounds.

Civic Participation

Throughout the late-1980s and 90s, CRF expanded its mission to more directly empower young people to informed, skilled, and effective citizens. Led by Todd Clark, CRF created a range of programs to actively engage young people in addressing problems in their schools and communities and through these experiences developing the habits of active civic participation.

Beginning with Youth Community Service and Youth Leadership for Action, teams of students from local schools organized projects to benefit their communities.

After the civil disturbances in Los Angeles in 1992, and funded by a range of public and private sources, CRF created Youth Task Force L.A. involving dozens of high schools to address community problems and promote positive change.

Through these efforts, CRF became a leader in the state and national service-learning movement, which sought to link service to actual classroom learning outcomes. CRF pioneered what might be called “civics-based service learning” to enhance student service by explicitly involving students in studying and evaluating public policy. Working with the CloseUp Foundation, CRF created the Active Citizenship Today model that eventually was incorporated into several state social studies frameworks and inspired other programs across the country. Then CRF developed CityYouth, an innovative program to meet the needs of middle schools with an inter-disciplinary curriculum and civic participation strategies. For high schools CRF created CityWorks, a program specifically for U.S. government courses providing teachers and students a curriculum for learning about local government while conducting rigorous projects by studying policy and actually addressing a community problem or issue.

Direct Service Programs

CRF’s more direct involvement with youth in its various civic participation programs spurred the organization to recognize the challenges that many young people face growing up in urban environments. Many from disadvantaged families have few connections with the kind of institutions, experiences, and role models that help propel children from other backgrounds into college and successful careers.

In the 1980s, CRF established the Compton Youth Center to serve area youth. Participants at the center conducted service projects, volunteered at community functions, and received home work help and mentoring.

In 1993, with support from a grant from the Department of Education, CRF developed a youth internship program to provide young people with opportunities to bridge the gap through intensive seminars and work experience in professional settings, particularly law offices. The seminar and work experience model proved to have a strong impact on participants, and when federal cutbacks curtailed funding for the third year, CRF decided to continue the program by seeking board member sponsorships and foundation scholarships for the participants.

In 1993, with support from a grant from the Department of Education, CRF developed a youth internship program to provide young people with opportunities to bridge the gap through intensive seminars and work experience in professional settings, particularly law offices. The seminar and work experience model proved to have a strong impact on participants, and when federal cutbacks curtailed funding for the third year, CRF decided to continue the program by seeking board member sponsorships and foundation scholarships for the participants.

The plan worked. Over the years, the program has been continually improved and, now called Expanding Horizons Internships, offers rigorous seminars on academic, civic, and professional development, including high-quality aid in the college application process, thanks to long-serving CRF Board Member Peggy Saferstein and her colleagues. Students are placed in a range of work experiences in law, business, entertainment, health care, and the public service sectors. And thanks to the generous support of donors and dedicated staff, now 20 years later, 1,400 deserving young people have benefited from this transformational experience.

In a similar vein, CRF developed a direct service program for young people interested in law and legal careers. Called Summer Law Institute, the program consisted of an intensive one-week experience during the summer. Participating students lived in the UCLA dorms, learned about law and the legal process, interacted with judges and lawyers, found out about law school, and even took part in an extended mock trial.

Responding to Crisis

In times of local and national crisis, teachers are often called upon to address the events and their emotional impact with their students in the classroom. Even highly competent and professional, teachers often lack the resources to take on this vital role. Over the years, CRF has developed a tradition and national reputation among educators of responding to the needs of schools and teachers in dealing with tough issues under emotional circumstances with balanced and effective resources.

In 1978, Los Angeles Unified School District faced a busing desegregation plan imposed by the Courts that led to widespread unrest and protest. CRF devoted an issue of Bill of Rights in Action to the issues involved and conducted workshops for teachers around city.

In the aftermath of the verdict in the Rodney King beating case, many areas in South and Central Los Angeles were torn by civil disturbances, arson, and looting. Fifty-three people died in the three days of rioting. Fires burned within blocks of the CRF offices. Even after order was restored, tensions remained as the federal criminal cases moved forward against the accused police officers. Teachers and community leaders faced anger as they tried to explain the legal and political issues raised in the aftermath, and fears mounted that new civil unrest would result if the officers were acquitted of the federal charges. Marshall Croddy and his publications team set to work to develop curriculum that could be used in the schools and in the community to explain the legal aspects of the cases and promote discussion and promote discussion of the social and racial issues roiling the city. As the federal trials moved forward, CRF delivered a well-researched 48-page curriculum called Reviewing the Verdict to schools around Southern California and worked with the Los Angeles County Bar Association to train volunteer attorneys in their use. In addition, CRF staff was enlisted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to make presentations at community meetings around the region as the verdicts in the federal trials approached in the spring of 1993.

Two years later, FEMA called again. In the aftermath of the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building, schools and community groups in Oklahoma were reeling from the tragedy and needed resources to educate about terrorism. Utilizing some of the strategies developed during the Los Angeles unrest, CRF developed a packet of materials and created a special Bill of Rights in Action on the topic of domestic terrorism for distribution around the nation.

In 1994, as Californians considered a controversial referendum (Proposition 187) on restricting the rights of unauthorized immigrants, Los Angeles High Schools faced boycotts and walkouts. The school district asked CRF to develop materials to explain the proposition and promote productive discussion for classroom use. CRF responded within two weeks with the Immigration Debate: Proposition 187 that was distributed to all LAUSD high schools.

In 1994, as Californians considered a controversial referendum (Proposition 187) on restricting the rights of unauthorized immigrants, Los Angeles High Schools faced boycotts and walkouts. The school district asked CRF to develop materials to explain the proposition and promote productive discussion for classroom use. CRF responded within two weeks with the Immigration Debate: Proposition 187 that was distributed to all LAUSD high schools.

Unrest over immigration policy erupted again in 2006 as thousands of students in Los Angeles and throughout California reacted to proposed federal legislation to drastically curtail illegal immigration by staging walkouts, freeway shutdowns, and massed protests in the Los Angeles Civic Center. Responding to an urgent call for curriculum from Los Angeles Board of Education Member David Tokovsky, who was trying to get students back to class from the steps of City Hall, CRF delivered a 48-page electronic curriculum within 72 hours. Called Current Issues of Immigration, the publication was distributed to schools around the area and state by LAUSD, the Los Angeles County Office of Education, and the California State Department of Education. Renewed protests erupted the next year prompting the development and distribution of a second edition.

Recognizing that issues of immigration were likely to continue to spark controversy, in CRF 2007 received a generous grant from the Weingart Foundation and developed a web site called Educating about Immigration containing free and updated classroom resources on the topic for classrooms to address the topic on an ongoing basis.

CRF also developed and distributed materials on the Gulf War, hate crimes, the 911 terrorist attacks, the impeachment of President Clinton, and America’s Economic Crisis and stands ready to respond again when the need arises.

A Commitment to Quality

Throughout its history, CRF has recognized the need to assure program and publication quality through extensive review, field testing, teacher and student feedback, assessment, and formal evaluation.

In the early 1980s, CRF participated in an evaluation of its Los Angeles Project Status program, again designed to reduce delinquent factors among students and found some of the most significant results ever reported in the field. Both of these studies have influenced CRF program design for many years.

Later in the 1980s CRF participated with it national partners in a rigorous study of the effectiveness of law-related education programs and found that if properly implemented, they could have a delinquency prevention effect. The study also identified criteria for the success of such programs.

In the 1990s, the evaluation of CityYouth showed the middle school program had both significant teacher and student impact with students improving problem-solving capacity, efficacy, and positive attitudes toward school. The experimental design research conducted on CityWorks in the early 2000s demonstrated that students in the program performed better on standard U.S. government content items than regular students and developed significantly greater civic capacities and competencies. The findings on the positive effect of simulations from the evaluation have been cited in national studies.

In the 1990s, the evaluation of CityYouth showed the middle school program had both significant teacher and student impact with students improving problem-solving capacity, efficacy, and positive attitudes toward school. The experimental design research conducted on CityWorks in the early 2000s demonstrated that students in the program performed better on standard U.S. government content items than regular students and developed significantly greater civic capacities and competencies. The findings on the positive effect of simulations from the evaluation have been cited in national studies.

More recently, through its California Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools program, CRF supported and participated in research replicating national studies on the positive effects of certain educational practices on the development of student civic competencies and capacities and led to findings that a civic education opportunity gap existed between white, college-bound students and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those of color, and those not college-bound. This research has influenced both policy and the development of proposed national legislation.

A two-year evaluation of CRF’s internships released in 2007, found that the program had important effects on the participants. It improved civic knowledge and attitudes, attitudes toward academic goals and success, and career skills and attitudes. It had an even greater impact on participants’ feelings of self-efficacy, achievement motivation, and civic-engagement capacities. Perhaps even more impressively, the study demonstrated that the positive effects of the program lasted over significant passages of time.

CRF Goes International

By the early 1990s, through its publications and hosting foreign civic educator visitors, CRF had had established an international connection. In the late 1990s, working with U.S. educational partners, it created the Democracy Education Exchange Project to work with educational partners in the former and newly independent Soviet republics, including Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Czechoslovakia, Serbia, and Croatia. The program featured international teacher conferences and teacher and curricular exchanges.

Then in the mid-2000s, working with Constitutional Rights Foundation/Chicago, the Foundation became a partner in Deliberating in a Democracy, a program that featured models for effective classroom discussion on topics important to all democracies. The program featured teacher professional development on the model and online international student forums that linked classrooms in Southern California and around the country with counterparts in East and Southeast Europe. In 2010, this model was adapted for a new effort called Deliberating in a Democracy in the Americas for Latin American countries including Mexico, Columbia, Ecuador, and Peru.

A Dedicated Staff

CRF has always benefited from the contributions of a dedicated, talented, and in many cases, long-serving staff. Its ranks have included teachers, lawyers, academics, and youth development professionals. Richard Weintraub joined the staff as associate education director in the early 70s and forged relationships with the local education community and developed local programming. Dr. Phyllis Maxey was instrumental in developing the Business in the Law program and served as its first director. Kathleen Kirby became CRF’s second associate education director and then education director and supervised CRF local and state programs for many years.

Cathy Berger Kaye was instrumental in the development of our early community service and service learning programs. Jennifer Appleton got our youth development programs on sound footing. Mock Trial has benefited from the leadership of several directors beginning with Eleanor Taylor and leading to our current long-term director, Laura Wesley.

Keri Doggett joined the staff as a temporary and rose through the ranks as office manager, program director, and is now Director of Program Development. Katie Moore, our current director of international programs, has also served in many capacities in our service learning and direct service programs. Sylvia Andresantos began as a receptionist and now manages our local law programs.

In publications, Coral Suter made significant contributions to our nascent publication program in the early 1980s through her research and writing skills. Bill Hayes, a former teacher and lawyer, has been the senior editor and writer at the foundation since 1991. Andrew Costly began as an administrative assistant at about the same time and now manages publications and all of our web resources.

Several of our employees began as participants in our programs. Lourdes Morales, our current History Experience Director, started her association with CRF as a student in Youth Community Service; Gregorio Medina became involved with CRF as a college mentor at the Compton Youth Center and is now a lead trainer for several of CRF’s civic engagement programs.

Carol Kest assisted Vivian Monroe in establishing modern development approaches. JoAnn Burton took over as development director in 1988 and has served in the function ever since, improving the Spring Dinner and other events. Lisa Reale, who made great contributions to the Bill of Rights Bicentennial as the Times Mirror community affairs director now serves CRF as a consultant on development and media outreach.

In the late 1980s, Hal Ellis, a retired executive, put CRF’s financial systems on a firm basis, followed by John Martin who still works with us today as a consultant. Casey Clevenger served for many years as CRF’s information and technology manager and then consultant, supported by long-term volunteer tech guru, James Hightower.

As it always has, CRF continues to attract a new generation of staff dedicated to our mission: Damon Huss, teacher trainer and writer; David De La Torre, program manager and videographer; Victor Monzon, Controller; Nancy Sanchez, Expanding Horizons Internship manager, Carlos Ramos, program coordinator, and Wilson Shum, IT coordinator.

Into the Digital Age

Recognizing the cost efficiency and potential impact of the Internet, CRF began utilizing the web to deliver program information and educational resources. By the early 2000s, CRF’s main web site featured information about all of its major programs, hundreds of free downloadable educational resources, live links to support CRF texts, and an online catalog.

Users of the site reached nearly 1.5 million unique visitors per year in 2007. The same year, the Los Angeles Times named it as the top academic “super-site” in its annual guide to educational resources for students on the web. In 2010, findingDulcinea, Librarian of the Internet, a noted web guide, named CRF among the “101 Great Sites for Social Studies” and one of eight on its “Top Sites for High School Government Teaching Resources.”

Based on this success and with the support of various funders, CRF began developing and launching specialty web sites to address specific programs and content areas and needs. Youth Forum (2004), California Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools (2005), and Deliberating in a Democracy (2006).

Based on this success and with the support of various funders, CRF began developing and launching specialty web sites to address specific programs and content areas and needs. Youth Forum (2004), California Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools (2005), and Deliberating in a Democracy (2006).

In 2007, CRF received funding to create web resources for teaching about immigration, intellectual property, and its most ambitious digital effort, Civic Action Project. This web resource serves teachers and students with online resources to learn about civics and government while actually engaging in projects to address community issues and problems, affect public policy pertaining to them, and promote constructive change.

On the retirement of Todd Clark, in 2008 CRF's Board of Directors selected Jonathan Estrin to serve as president and Marshall Croddy as vice president. In 2013, CRF selected Marshall Croddy to be its president. Croddy's breadth of knowledge and wealth of experience in both civic education and CRF programs and partners make him the ideal person to drive this organization forward.

In 2023, Constitutional Rights Foundation changed its name to Teach Democracy.

SOURCES

Anonymous. Articles of incorporation of Los Angeles Civil Liberties Foundation. Constitutional Rights Foundation Archives. July 15, 1957

Certificate of amendment of articles of incorporation. Constitutional Rights Foundation Archives. December 12, 1963

California’s progress in teaching the Bill of Rights. Constitutional Rights Foundation Archives. 1966

Survey of Constitutional Rights Foundation Programs. 1963-1970. Constitutional Rights Foundation. 1970.

Constitutional Rights Foundation Annual Reports, 1970s-2004

2011 Spring Dinner Past Honorees and Speakers, Constitutional Rights Foundation Document.

Constitutional Rights Foundation Annual Summary. 1971

Constitutional Rights Foundation Annual Summary. 1972

Constitutional Rights Foundation 1972-1975, Program Summary. Constitutional Rights Foundation. 1975

CRF Publications Archive, 1977-2007

Croddy, M.. Interview with Todd Clark. May 1991

Croddy, M. Interview with Vivian Monroe. May 1991

Croddy, M. Interview with JoAnn Burton. February 2012

Research and Evaluations of CRF Programs, CRF Main Website, crf-usa.org. 2012

Constitutional Rights Foundation WebCitizen Prospectus, Unpublished. 2010

Croddy, Marshall, Bringing the Bill of Rights to the Classroom, The Social Studies, California Council of the Social Studies. 1991