CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS FOUNDATION

Bill of Rights in Action

FALL 2010 (Volume 26, No. 1)

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom | Plato and Aristotle on Tyranny and the Rule of Law | Nigeria

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom: The Road to the First Amendment

Many colonists came to America to escape religious persecution. But colonies soon adopted laws that limited religious freedom and forced to people to pay taxes to support churches they did not believe in. Dissenters started protesting to abolish those laws. An important change came in 1786 when Virginia passed the Statute for Religious Freedom. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, the new law served as a model for the First Amendment. It established a clear separation of church and state and was one of Jefferson’s proudest accomplishments.

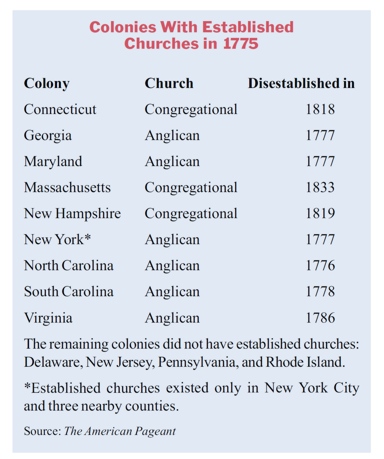

Most of the early colonists in America came from England. Many who settled in the South—the Plantation colonies—belonged to the Church of England, or Anglican Church. In Virginia, ministers were required to preach Christianity according to the “doctrine, rites and religion” practiced by the Church of England. A law passed in 1611 required everyone to attend church on the Sabbath. A later law imposed a tax to pay for church ministers’ salaries and to build new churches, and it allowed only Anglican clergymen to perform a marriage ceremony. Similar establishment laws were passed in North and South Carolina and in Georgia.

In Maryland, the Church of England was also the established church. Because many Catholics lived in Maryland, the colony passed an Act of Toleration in 1649. The law provided toleration to all Christians, but it also decreed a death penalty for people, like atheists or Jews, who denied the divinity of Jesus.

In New England, colonists also passed laws involving the government in religion. Most of the early settlers in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire were Puritans who belonged to the Congregational Church. For the first 50 years in the Bay Colony—which became Massachusetts—no resident of the colony could vote unless he belonged to the Congregational Church. Later laws required each town to maintain an “able, learned and orthodox minister” paid for by the town’s taxpayers. Because Congregationalists were in the majority in most towns, the law left others, like Episcopalians, Baptists and Quakers, out in the cold. Similar laws existed in Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York City, and other parts of New York.

1776 and Freedom of Worship

On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia approved the Declaration of Independence. Two months earlier, a Virginia convention had already declared independence from England and called on the other colonies to do the same. As in Philadelphia, the delegates in Virginia decided to write a document stating the moral basis for their decision. They produced the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which included a list—or “bill”—of rights. Article 16 was drafted by George Mason and by a 25-year-old delegate named James Madison. (Later, Madison became known as the “father” of the U.S. Constitution and was elected the fourth president of the United States.)

Madison’s draft provided that “all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.” The Virginia Declaration’s promise of full freedom of religion generated enthusiasm among the colony’s non-Anglicans. They were becoming increasingly angry about the restrictions the established church imposed on them.

Dissenters had been petitioning in Virginia since 1772 to change the laws that gave special privileges to the Anglican Church. They wanted an end to the taxes that supported the established church. They wanted their clergy to be allowed to perform marriages. And they wanted to abolish the law that required non-Anglican clergy to apply for a license and to get authorization for holding a religious service. The number of Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians was growing, and their call for more religious freedom became louder when Article 16 of the Declaration of Rights was passed on June 12, 1776.

Bill No. 82: The Fight to Separate Church and State

In the autumn of 1776, Virginia’s new House of Delegates met and welcomed back Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was 33 years old and already an important figure. He had been a delegate to the Continental Congress and was the author of the Declaration of Independence. Now back in Virginia, Jefferson decided to help create a new form of government for his state. In October, he proposed a complete revision of the state’s laws. Key among the laws that Jefferson believed needed to be rewritten were the restrictions on religious freedom. Jefferson strongly believed not only in freedom of worship, but also in an end to all control and support of religion by the state.

After two years of work, Jefferson and his Committee of Revisors presented a list of 126 proposed laws to the Virginia Assembly in June 1779. Many of the new laws were minor changes. But Bill No. 82 was a major change. Drafted by Jefferson, the bill removed all links between religion and government. In a lengthy preamble, the bill laid powerful reasons for de-establishing religion. It is, Jefferson wrote, “sinful and tyrannical” to compel a man to furnish contributions of money “for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors. . . . Our civil rights,” he wrote, “have no dependence on our religious opinions, any more than our opinions on physics and geometry.” Be it therefore enacted, the Bill stated:

that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever . . . nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of Religion . . . .

Bill No. 82 was not the only bill before the Assembly concerning religion. Churchmen, worried about losing public support for their ministries, introduced a compromise General Assessment bill. Under the General Assessment bill, any church subscribed to by five males over the age of 21 would become a Church of the Established Religion of the Commonwealth and receive state support. The Legislature thus faced two contradictory bills about a subject that aroused deep emotions and concerns among Virginians.

The fight over whether to have an established church continued for almost six years. Patrick Henry introduced a modified version of the General Assessment bill in 1784. Henry was a popular hero, who had just served three one-year terms as governor. His bill was also a “multiple establishment” bill. It provided for an annual tax to support the Christian religion or “some Christian church, denomination or worship.” It was supported by many of the most powerful men in the Legislature and backed by Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Methodists. Jefferson’s bill was supported by Baptists and evangelicals, who generally believed in the principle of voluntary support.

Jefferson was not present during the six years that the Legislature was fighting about religion (serving as governor, congressman, and then as minister to France). The job of passing Bill No. 82 fell to James Madison, a skillful politician and close ally of Jefferson. In the summer of 1785, Madison wrote a dramatic petition titled “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments.” Madison urged the Legislature not to pass the General Assessment bill, arguing that religion should be exempt from the authority of any Legislative body and left “to the conviction and conscience of every man.”

Religion, he wrote, is a right like other rights and liberties, and if we do not want to allow the Legislature to “sweep away all our fundamental rights,” then we must say that they must leave “this particular right untouched and sacred.” Madison believed that giving the state control over religion would be the same as allowing it to control—and limit—other important liberties as well:

Either we must say, that they may controul the freedom of the press, may abolish the Trial by Jury, may swallow up the Executive and Judiciary Powers of the State; nay that they may despoil us of our very right of suffrage, and erect themselves into an independent and hereditary Assembly or, we must say, that they have no authority to enact into the law the Bill under consideration.

Copies of Madison’s Memorial were distributed throughout the state and helped create a storm of popular protest. The Memorial was signed and sent to the Legislature by thousands of residents who opposed the notion of an established church. Numerous other petitions with over 11,000 signatures were also sent to legislators’ desks, and nine out of 10 condemned the bill for General Assessment. Responding to the public outcry, when the Legislature reconvened in January 1786, it passed Jefferson’s bill by a margin of 60 to 27.

No National Church: The First Amendment

A year after Virginia enacted the Statute for Religious Freedom, the U.S. Constitution was drafted and sent to the states for ratification. James Madison, the person most instrumental in writing the new Constitution, passionately supported it. When a convention met in Virginia to consider ratification, many delegates opposed the Constitution because it did not include a bill of rights to protect important liberties like freedom of religion.

A year after Virginia enacted the Statute for Religious Freedom, the U.S. Constitution was drafted and sent to the states for ratification. James Madison, the person most instrumental in writing the new Constitution, passionately supported it. When a convention met in Virginia to consider ratification, many delegates opposed the Constitution because it did not include a bill of rights to protect important liberties like freedom of religion.

Madison argued that the Constitution did not need a bill of rights. Congress had no authority over religion, and Virginia, like many other states, had its own constitution that included a Bill of Rights. But to satisfy the opposition, he promised that as soon as the Constitution was ratified, he would propose amendments to include a Bill of Rights.

Madison kept his promise. The U.S. Constitution was officially ratified in June 1788, and the First Congress met in New York in March 1789. Three months later, on June 8, 1789, Congressman James Madison from Virginia rose and proposed a series of amendments. The section on religion read:

The Civil Rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, nor on any pretext infringed.

In September, after three months of debate, Congress passed a revised clause protecting religious freedom in the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . . .

When the First Amendment passed, three states still had laws providing government support for churches. But with the establishment clause in place, the United States had no power to establish a national religion or to support multiple establishments of the Christian church.

After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment was enacted. In later rulings, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the 14th Amendment incorporated all the protections of the First Amendment. That means the First Amendment today guards against establishment laws passed by state and local government as well those passed by the national government.

Jefferson’s Role in the Statute

|

A Bill Establishing a Provision for Whereas the general diffusion of Christian knowledge hath a natural tendency to correct the morals of men, restrain their vices, and preserve the peace of society; which cannot be effected without a competent provision for learned teachers, who may be thereby enabled to devote their time and attention to the duty of instructing such citizens, as from their circumstances and want of education, cannot otherwise attain such knowledge; and it is judged that such provision may be made by the Legislature, without counteracting the liberal principle heretofore adopted and intended to be preserved by abolishing all distinctions of pre-eminence amongst the different societies or communities of Christians . . . . This is the preamble to Patrick’s modified version of the General Assessment bill. It sets out his reasons for supporting his bill. |

The U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment incorporated the principles stated in the Statute of Religious Freedom. The statute was passed largely through the hard work of James Madison, and Madison also played a significant role in drafting the First Amendment and in shepherding it through Congress. But the guiding light behind the statute was its author, Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson believed strongly that religious beliefs should be solely a matter of individual conscience. He wrote in a January 1802 letter to a group of Baptists:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man & his God . . . , that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.

The Supreme Court has used the phrase “wall of separation between Church and State” in many of its First Amendment opinions. “Coming as this does from an acknowledged leader of the advocates of the measure, it may be accepted almost as an authoritative declaration of the scope and effect of the amendment thus secured,” wrote U.S. Chief Justice Waite in the case of Reynolds v. U.S. (1878).

Jefferson took great pride in his role in bringing religious freedom to Virginia and ultimately to the United States. Evidence of that pride is the epitaph for his tombstone, which he wrote near the end of his life. He did not want mentioned that he had served as president of the United States, secretary of state, governor of Virginia, or minister to France. Instead, his tombstone reads:

Here was Buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the

Declaration of American Independence

of the

Statute of Virginia

for

Religious Freedom

and Father of the

University of Virginia

For Discussion

1. What is an established church? Cite examples from the article of different types of establishment laws. What are problems that might arise from establishment laws?

2. What was the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom? Who favored it? Who opposed it? Why was it important? Why do you think Jefferson was so proud of it?

3. The First Amendment, in part, reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . . .” What does it mean?

4. Other democracies, such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Israel, have established religions. Do you think individual states or the United States should have an established religion? Why or why not?

A C T I V I T Y

Madison vs. Henry

James Madison worked hard to get the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom passed. His main opponent was Patrick Henry, who offered a counter bill. Henry delivered a series of speeches in favor of his bill. They were so powerful that they prompted Madison to write his “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” which met widespread approval and led to the Legislature passing the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

In this activity, you are going to role play Madison and Henry and debate which bill should be supported.

1. Form groups of seven. Select two members to role play Madison and a colleague, two members to role play Henry and a colleague. The other three role play members of the Virginia Legislature.

2. The Madison and Henry teams should prepare arguments for their sides using information from the article (both sides should be sure to look at the sidebar “A Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion,” which is the preamble to Henry’s bill).

3. The three other members of each group should prepare questions to ask each side.

4. When both sides are ready, they should hold a debate over their respective bills.

5. When done, the whole class should discuss the best arguments they heard in their group and what made them powerful arguments.|