CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS FOUNDATION

Bill of Rights in Action

WINTER 2010 (Volume 26, No. 2)

The “Black Death”: A Catastrophe in Medieval Europe | The Potato Famine and Irish Immigration to America | The Debate Over World Population: Was Malthus Right?

The Debate Over World Population: Was Malthus Right?

In 1798, English economist Thomas Robert Malthus wrote an essay predicting that if humans did not check their fast-growing numbers, mass starvation would result. A debate over Malthus’ gloomy outlook ignited during his lifetime and is still going on today.

The debate over the limits of human population growth began with Greek and other ancient thinkers. In A.D. 210, Tertullian, an early Christian scholar, wrote:

Our teeming population is the strongest evidence our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly support us from its natural elements. . . . In every deed, pestilence and famine and wars have to be regarded as a remedy for nations as the means of pruning the luxuriance [large numbers] of the human race.

At the time of the American and French revolutions in the late 1700s, some English and French writers predicted unending improvement for humankind. William Goodwin, an English philosopher, wrote about a bountiful earth capable of supporting the growing human population indefinitely.

Not everyone agreed with this optimistic vision of the future. Thomas Robert Malthus, a professor of economics in England, held a much more pessimistic view.

Malthus’ Principle of Population

In 1798, Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population, as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society. Malthus began with two “fixed laws of our nature.” First, men and women cannot exist without food. Second, the “passion between the sexes” drives them to reproduce.

He explained that, if unchecked, people breed “geometrically” (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc.). But, he continued, the production of food can only increase “arithmetically” (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.). “The natural inequality of the two powers of population and of [food] production in the earth,” he declared, “form the great difficulty that to me appears insurmountable [impossible to overcome].”

Malthus concluded: “I see no way by which man can escape from the weight of this law.” In other words, if people keep reproducing in an uncontrolled geometric manner, they will eventually be unable to produce enough food for themselves. The future, Malthus argued, pointed not to endless improvement for humanity, but to famine and starvation.

Malthus claimed that, if unchecked, the population of a nation or even the world would double every 25 years. He got this idea from Benjamin Franklin, who had estimated that 1 million American colonists, living in an abundant and healthy environment, would double to 2 million in 25 years.

Malthus applied this doubling rule to Britain, with a population he estimated at 7 million. He calculated that in 25 years Britain’s population would reach 14 million, but food production would keep up. In another 25 years, the population would redouble to 28 million. Food production, however, increasing at the slower arithmetic rate, would only feed 21 million. Malthus recognized that his doubling rule would only apply in situations of continuous uncontrolled childbirth.

Malthus noted that the English poor added to their own misery when they married early and had too many children during good times. These children grew up to create an oversupply of workers and a drop in wages. Meanwhile, the population increase caused by their large numbers stressed food production and caused higher prices. The result, said Malthus, was hunger and a rise in child mortality (death).

Malthus argued that these conditions forced the poor to marry later and have fewer children, which brought the population and food supply back into balance. But as soon as things got better, the poor produced greater numbers of children again, and the whole cycle started again.

Malthus contended that the only way to avoid mass starvation in the future was to check population growth to keep it equal to food production. He declared, “The superior power of population cannot be checked without producing misery and vice.” By “misery and vice,” he meant starvation, plagues, war, contraception, abortion, and the killing of infants, none of which he wanted to see happen.

Was there nothing other than “misery and vice” to control population? In his book-length 1803 revision, Malthus called for “moral restraint,” which included chastity until marriage, delayed marriage, and having fewer children (he had five).

Malthus did not believe “moral restraint” would work, especially among the poor. Even so, he supported a public tax-supported primary school system to lift the lower classes out of poverty and irresponsible breeding and into middle class self-control and responsibility.

But Malthus vehemently opposed giving government relief, such as food and shelter, to the impoverished. Making the poor comfortable, he argued, only encouraged them to have bigger families, which increased their numbers and continued their misery.

Malthus Debunked

After Malthus first published his essay in 1798, a storm of criticism erupted. The optimists called his vision of unavoidable mass starvation a “doctrine of despair.” Others condemned his call for abolishing England’s Poor Laws, which provided relief for the starving homeless. The historian Thomas Carlyle dubbed Malthus’ new subject of economics the “dismal science.”

Malthus and others who came to his defense, like economist David Ricardo, became the pessimists in the debate over the future of humanity. Over time, however, Malthus became slightly more hopeful about the future. He admitted the possibility of “gradual and progressive improvement in human society.” When he died in 1834, the population of the world stood at about 1 billion people.

Ironically, during Malthus’ lifetime, England was radically changing. The Industrial Revolution and the use of machinery in agriculture greatly multiplied what each factory and farm worker could produce.

Malthus did not foresee the possibility of opening up vast new tracks of land for cultivation by steam-powered farm machines. Now, fewer farmers could produce more food than ever before. Thus, Malthus’ “arithmetic” increase in food production seemed far too limited.

Later on, something unexpected happened as the Industrial Revolution modernized Europe. No longer needed for agricultural labor, people moved to industrial cities. Here they discovered less need for large families than on the farm where children helped with the planting, harvests, and other chores. Also, since health conditions improved, child mortality declined. People discovered they did not have to have large families to compensate for some of their children dying young.

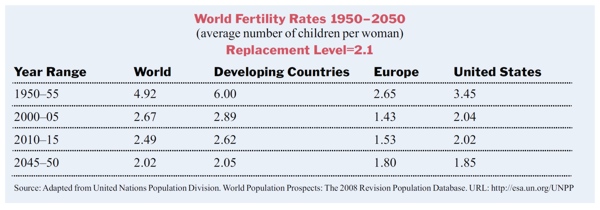

By 1900, in many parts of Europe, the fertility rate (average number of children born per woman) began to go down. This meant smaller families. This check on population growth was one Malthus never imagined.

Demographers, who study population trends, have discovered other reasons why families get smaller when a society modernizes. As poor women from farm regions become better educated, they tend to seek work outside the home, delay marriage, and have fewer children when they do marry.

In countries that have undergone modernization, married women often choose to have a job and a family, but with only one or two children. Many parents also choose between having a large family that may cause financial struggle or a having a small family that may allow a more comfortable lifestyle.

Thus, as a nation industrializes and its people become better educated, the fertility rate seems to drop, which means smaller families and a slowing of population growth. Economists call this the “demographic transition.”

By the 20th century, improvements in agriculture had sped up food production and the “demographic transition” had slowed down population growth. The old debate between the optimists and the pessimists appeared to be over. The optimists had won, and Malthus’ Principle of Population seemed dead.

The Return of the Pessimists

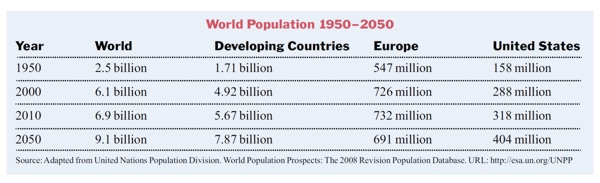

After World War II, the world’s population accelerated. It took more than 100 years for the population to grow from 1 billion in Malthus’s time to 2.5 billion 1950, an increase of 1.5 billion. It only took 25 years, however, to add another 1.5 billion between 1950 and 1975. This occurred mainly because death rates from disease fell sharply in many nations due to better health care.

The increasing world population alarmed some environmentalists, who declared that since the earth’s resources were limited, population had to be controlled or even reduced. Of course, this was the basic argument made by Malthus and his fellow-pessimists over a century earlier.

Fears of an overpopulated planet became a hot topic when Paul and Ann Ehrlich published The Population Bomb in 1968. “The battle to feed all humanity is over,” the Ehrlichs pronounced. “In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.”

Population numbers continued to zoom upward, doubling in 40 years from 3 billion in 1960 to 6.1 billion in 2000. In its mid-range estimate, the United Nations projects the world population to reach 8 billion by 2025 and 9.1 billion by 2050 at a pace of 78–80 million people per year. Some predict that if population numbers do not taper off in the second half of the 21st century, the world’s population may reach 11–12 billion by 2100.

The driving force behind this mounting population is the high fertility of women in poor developing countries, such as Pakistan currently at 4.0 children per woman and Uganda with 5.9. (The world average is 2.5 children per woman.) Moreover, many people in these poor countries are young and have not reached child-bearing age.

In 1968, Paul and Ann Ehrlich, along with other population pessimists, argued that the world’s population was outracing the food production. In the 1970s, however, biologists developed new high-yield strains of wheat, rice, and other food crops that dramatically boosted harvests, much like steam-powered farm machinery did over a century ago. Many agricultural experts called this the Green Revolution.

Thus, food production again kept up with population growth. But this came at a cost. The new high-yield seeds required chemical fertilizer and pesticides, too expensive for many farmers in poor countries. Also, the Green Revolution crops depleted soil faster, and the fertilizers and pesticides polluted waterways.

The Green Revolution may have prevented the mass-starvation predicted in The Population Bomb, but the pessimists point to local and regional famines that still kill millions of people today when droughts, floods, and pests destroy crops. In addition, climate change may intensify these threats. In 2010, an unprecedented drought and wildfires destroyed much of the wheat crop in Russia, a major world grain exporter.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 20 percent of the people in poor developing countries are “chronically undernourished.” The FAO also states that food production must increase by 70 percent to feed adequately the 9 billion people expected to inhabit the planet by 2050. The pessimists doubt that science has enough time to find and crossbreed genes from wild plants to develop new high-yield food crops.

Today, the population pessimists emphasize the environmental damage and depletion of natural resources caused by an overpopulated planet. They point to eroded and exhausted farmland, pollution, shrinking forests, and declining non-renewable energy like oil. Currently, Egypt and neighboring African countries with some of the highest fertility rates in the world are battling over how much water from the Nile each should get for irrigated farming.

The pessimists argue that the “demographic transition” takes a long time to develop. In many countries, cultural and religious traditions stand in the way, especially blocking any changes in the role of women.

Even as the fertility rate drops in countries going through the “demographic transition,” the pessimists contend, the resulting smaller but wealthier families typically consume more of the earth’s resources. They have richer diets and live in bigger houses. Imagine every Chinese adult in a country of 1.3 billion people owning and driving a car.

How many people can the earth support? Recent researchers have tied their estimates to some level of well-being for the earth’s inhabitants, including such things as diet, shelter, possession of manufactured goods, etc. Most of these estimates put the earth’s “carrying capacity” at between 4 and 16 billion people.

About 40 years after Paul and Ann Ehrlich published the Population Bomb, the world’s population has nearly doubled again. The pessimists call for stepped up U.N. and national programs to bring down the fertility rate in poor developing countries. Men and women, say the pessimists, need instruction on family planning, delayed marriage, and the economic advantages of smaller families as well as easy access to contraceptives.

The Optimists Strike Back

Today’s population optimists point out that while the total number of people in the world is still going up, the yearly rate of population growth has been declining sharply, except in poor developing countries. The optimists expect the world’s population to peak at about 9 billion in 2050 and then gradually go down.

Optimists say that the decrease in the world fertility rate has been even more dramatic: 4.9 children per woman in 1950 to 2.5 in 2010. Fertility rates have dropped the fastest in developed countries like Germany and Japan.

The optimists predict that by 2050 a majority of countries, including many poor developing ones, will be at or under the 2.1 fertility replacement level. This level occurs when parents, on average, have just enough children to replace themselves. (The .1 is a statistical adjustment to account for girls who die before childbearing age.)

The optimists argue that if we have a population problem in the future, it will be because fertility rates are too low in many nations. Developed countries like Germany and Japan already have fertility rates below the replacement level. They are facing the challenges of a decreasing and older population, labor shortages, and a shrinking economy. One solution for countries with negative population growth would be to encourage more young immigrants, who can increase the workforce and pay taxes to support the aging native population.

Unlike most other developed countries, the United States is on track to have a steadily rising population through 2050 even though its fertility rate has been below the replacement level since the 1970s. Demographers say the U.S.’s population will rise because of continuing immigration.

The widespread famines and mass-starvation predicted in The Population Bomb never happened. The optimists say the world now produces more food on less land than ever before. Still, large areas of land suitable for farming have yet to be cleared for cultivation.

The optimists point to the Green Revolution, which boosted world food production 250 percent. As a result, food prices have gone down, calories per person are up, and malnourishment is more the result of stalled economic development and wars. In the meantime, life expectancy around the world has steadily climbed.

As for threats to the environment and depletion of resources, the optimists like to quote economist Julian Simon who wrote The Ultimate Resource in 1981:

Human beings are not just more mouths to feed, but are productive and inventive minds that help find creative solutions to man’s problems, thus leaving us better off over the long-run.

There is no reason, according to the optimists, why inventive scientists and others cannot develop new nutritious food crops, discover energy alternatives, or use technology to heal the environment.

The optimists have long objected to the aggressive population control policies of the pessimists as unnecessarily invading the lives of people, especially poor women. For decades after World War II, the U.N. and many nations adopted policies that encouraged the use of contraceptives, voluntary sterilization, and abortion to reduce fertility in regions of high population growth.

The most extreme population control measure was China’s one-child policy. This successfully reduced China’s fertility to below the replacement level. The Chinese tradition of favoring boys over girls, however, led to an upsurge of abortions among some women to secure a male as their single child. This has caused an imbalance of males in China’s population.

The optimists call for an end to what they call the “war on fertility.” They are convinced that economic development and education, especially of women, in the high fertility developing countries will speed the “demographic transition.” This will naturally reduce the fertility rate and slow population growth to enable a balance between numbers of people and the “carrying capacity” of the earth.

For Discussion

1. What was Malthus’ Population Principle? How did the Industrial Revolution appear to debunk it?

2. Pakistan with a current fertility rate of 4.0 is on track to see its population nearly double in the next 40 years. If this country had a choice between building dams to irrigate more farmland or increase investment in family planning to sharply reduce the fertility rate, which would you recommend? Why?

3. Make lists of the ways to control population growth suggested by Malthus, today’s pessimists, and today’s optimists. Pick what you think is the best suggestion from each list and explain why.

For Further Reading

Appleman, Philip, ed. An Essay on the Principle of Population. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

Newbold, K. Bruce. Population Geography, Tools and Issues. Lantham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

A C T I V I T Y

Is There an Overpopulation Problem?

Divide the class into three groups to debate this question. One group will take the position of the population pessimists, one group will take the position of the population optimists, and the third group will act as a panel of judges to decide the outcome of the debate.

1. The pessimists and optimists should first discuss among themselves what their answer to the debate question is based on the information provided in the article. Then, each side should research facts and arguments from the article to support its position.

2. The panel of judges should prepare questions to ask each side during the debate.

3. The debaters for each side should share researching, presenting their case, and answering questions from the judges and the opposite side.

4. After each side has finished presenting and answering questions, the panel of judges will meet openly before the debating groups and discuss the debate question. Panel members will conclude their discussion with a vote to decide the winner of the debate.