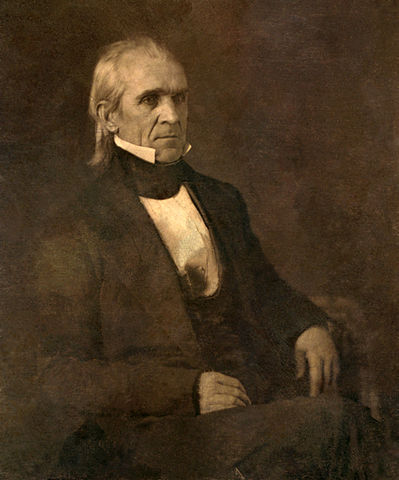

President Polk and the Taking of the West

President James K. Polk went to war with Mexico and got California and other lands in the West. The war's aftermath brought forward issues of the citizenship status and property rights of Mexicans who remained in the new American territories.

President James K. Polk went to war with Mexico and got California and other lands in the West. The war's aftermath brought forward issues of the citizenship status and property rights of Mexicans who remained in the new American territories.

Since the 1820s, Mexico had encouraged Americans to settle in its state of Texas. By the 1830s, Americans outnumbered native Mexicans in Texas by four to one. When a new Mexican constitution did away with state rights, the American settlers rebelled and established an independent country in 1836. Mexico, however, did not formally recognize the Republic of Texas.

Texas claimed the boundary with Mexico was at Rio Grande River. Mexico argued that it was at the Nueces River. The land in between these rivers included thousands of square miles and a few hundred settlers, few of whom were Texans.In 1845, Congress voted to annex Texas and admit it as a state. Shortly afterward, James K. Polk took office as the new U.S. president. Polk was a Democrat and a strong advocate of national expansion.

President Polk had a short list of "great measures" he intended to accomplish. Among them was the acquisition of Mexican California. Gold had not been discovered there yet, but Polk wanted California and its magnificent San Francisco Bay as the American gateway to trade with China and other Asian nations. Polk was worried that other nations, such as England or France, might take California if the United States did not act.

Using Texas to Get California

While Texas was ratifying its annexation to the United States, an American naval officer apparently tried to provoke a war with Mexico. Commodore Robert Stockton attempted to persuade Texas officials to move their militia into the disputed land between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers. This move would have resulted in a military clash with Mexican troops, which would have led to war with the United States when Texas was officially annexed. The objective was to quickly defeat the weaker nation and demand that it hand over its California and New Mexico territories. But the scheme failed when the president of the Republic of Texas objected and negotiated a peace treaty with Mexico. Historians disagree on whether President Polk was involved in this adventure.

In November 1845, President Polk sent John Slidell to Mexico City in an attempt to buy California and New Mexico. Mexico, in political and economic disarray, had failed to make payments on $4.5 million it owed the United States. Polk authorized Slidell to forgive the debt and pay another $25 million in exchange for these Mexican lands. Mexican officials, however, refused to meet Slidell. Even so, military opponents of the Mexican president considered Slidell's mere presence in Mexico City an insult. They overthrew the president and installed a new regime that favored war with the United States.

When Slidell reported on his failed mission to President Polk early in 1846, Texas had become the 28th U.S. state. Polk declared that the border between the United States and Mexico extended to the Rio Grande. He ordered American troops to cross into the contested land as a "defensive" act.

In March 1846, General Zachary Taylor led American troops across the Nueces River all the way to the Rio Grande. When Mexicans objected, Taylor positioned his troops across the river from the Mexican town of Matamoras. A few days later, some Mexican soldiers crossed the Rio Grande and attacked Taylor's men, killing 16.

When news came of the clash with Mexican soldiers, President Polk announced that the United States had been attacked. "American blood on the American soil," he said in his message to Congress, asking for a declaration of war against Mexico.

With Polk's party in the majority, Congress voted for war after two days of debate. Some members of Congress believed it was the "manifest destiny" of the United States to occupy all the land from the Atlantic states to the Pacific Ocean. Southerners saw an opportunity to create more slave states.

American forces defeated the Mexicans in California and New Mexico within a few months. In March 1847, General Winfield Scott invaded Mexico at the port of Vera Cruz and began to march inland toward Mexico City. The Mexicans did not win one battle in this war, but they fought fiercely and stubbornly refused to surrender.

The war was popular in the South and with Americans who believed in manifest destiny. But the war aroused great opposition. Congressman Abraham Lincoln introduced a "Spot Resolution," demanding that Polk show the spot where Mexicans "shed American blood on American soil." Lincoln proclaimed, "That soil was not ours; and Congress did not annex or attempt to annex it." Writer Henry David Thoreau went to jail for refusing to pay a poll tax in protest against the war. (He later wrote his essay "Civil Disobedience" explaining his action.)

In April 1847, amid increasing criticism of "Polk's War," the president sent a State Department official to Mexico to try to negotiate a peace treaty. Nicholas Trist was an unusual negotiator. He not only strived to end the war, but even sympathized with Mexico's grievances against Polk. Nevertheless, he was a professional diplomat who was determined to achieve his president's minimum goals of settling the border dispute and acquiring California and New Mexico.

After a cease fire had been arranged, Trist met with Mexican diplomats appointed by Mexican President Santa Anna. The negotiators could not reach agreement, and the war resumed. Soon, General Scott's army occupied Mexico City, forcing the Mexican government to relocate.

President Polk decided to recall Trist to Washington. But Trist disobeyed his orders and remained to try one more round of negotiations. These succeeded, and a peace treaty was signed at the city of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo recognized the border between the state of Texas and Mexico at the Rio Grande River. The United States also got California and New Mexico. (The Territory of New Mexico, later enlarged by the Gadsden Purchase, was eventually divided up into the states of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming.) The United States agreed to pay the Mexicans $15 million for giving up about half of their country.

Citizenship and Land Grants

Citizenship and Land Grants

The peace treaty was vague about the citizenship of Mexicans remaining in California and New Mexico. The treaty stated that Mexicans had the right to became American citizens who would be "admitted at the proper time" by Congress. In the meantime, their rights to liberty, property, and religion were to be "maintained and protected . . . without restriction."

The most troublesome problem resulting from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo concerned the ownership of Mexican land grants in California. Before the war, the Mexican government had approved more than 500 grants of land to California Mexicans (called "Californios") and even a few Americans. In most cases, the grant holders used their land to graze cattle for hides and beef.

The original treaty negotiated by Nicholas Trist flatly declared all Mexican land grants "shall be respected as valid." But President Polk and the U.S. Senate removed this provision before the treaty was ratified. Only a few general references to Mexican property rights remained in the treaty.

Almost as soon as the United States and Mexico ratified the peace treaty, gold was discovered in California. After a while, discouraged gold seekers began looking for land to settle. They soon learned that the best farm and grazing areas were already taken by the Mexican land grants, mostly held by a few hundred Californio families. The land-hungry immigrants began to challenge the property rights of the Californios, who had not yet been recognized as American citizens.

To settle the conflict over the California land grants, Congress passed the Land Act of 1851, which established a Board of Land Commissioners. This board was to verify or reject each California land grant claim.

The Land Act required all grant holders to appear before the Board of Land Commissioners and prove with documents and testimony the validity of their claims. In other words, the burden of proof was on the grant holders and not those who might challenge them. Moreover, once the commissioners made their decision, it usually was appealed to the federal courts, sometimes all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Board of Land Commissioners generally acted fairly and often understood that some documents, maps, or other evidence could not be presented because they had been lost over the years. The commissioners ended up confirming 75 percent of the grant claims, which included about 10 million acres of land. But the long, drawn-out verification process and court appeals cost a lot of money. Many of the land-rich and cash-poor Californios had to mortgage their land at high interest to pay their legal fees.

Other problems plagued the Californios while they tried to prove their claims. Lawyers swindled some of them. Land taxes, unknown in Mexican California, put the Californios further in debt. Squatters, hoping the Californios' claims would be rejected, moved onto their lands. The squatters fenced off homesteads, stole cattle, and sometimes violently forced the Californios out of their own homes.

By the 1860s, most of the Californios who had finally confirmed their grants still lost their land to the Americans due to overwhelming debts aggravated by plunging cattle prices and drought.

In 1870, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that Californios became full citizens when California was admitted as a state in 1850. Mexicans in the vast Territory of New Mexico were also eventually admitted as American citizens.

For Discussion and Writing

- Texas was annexed because Americans settled there and eventually revolted from Mexico. Had there not been a Mexican War, do you think this also would have happened in California? Explain.

- Who do you think was responsible for starting the war with Mexico in 1846? Why?

- Do you think the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was fair? Why or why not?

- Many American squatters argued that it was not fair for a small number of Californio families to monopolize the best agricultural lands in the state. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

For Further Information

An Outline of American History: Texas and the War With Mexico By From Revolution to Reconstruction.

Remember the Alamo From PBS's American Experience.

The Alamo From the American West.

Reader's Companion to American History: The Mexican War

Digital History: Hypertext History

Texas Question in American Politics

U.S.-Mexican War From PBS.

Key Events in the Mexican-American War A time line.

The Mexican-American War From the History Guy.

Enough Blame to Go Around: Causes of the Mexican-American War An AP history paper by John Heys.

The Mexican War and Hispanic Land Dispossessions By Ingolf Vogeler.

Spartacus Educational

The Mexican War From Lone Star Internet.

Invasión Yanqui: The Mexican War By the Texas Council for the Humanities Resource Center.

The Mexican War—a 1911 Explanation From a U.S. textbook of the era.

The Mexican War and After Extracted from American Military History.

U.S.-Mexican War By the Descendants of Mexican War Veterans.

Freedom: A History of US: Manifest Destiny

Texas Declaration of Independence, March 2, 1836

The Annexation of Texas Joint Resolution of Congress March 1, 1845

Message of President Polk, May 11, 1846

Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago, February 2, 1848

Mexican-American Diplomacy: 1848-1861 Documents from the Avalon Project.

Interactive Maps (require Shockwave)

Expansion of the United States Map showing expansion year by year from 1650 to 1907.

Internet Public Library: James Knox Polk

The White House: James K. Polk

North Carolina Historic Sites: James K. Polk Memorial

Polk Ancestral Home: A Biography

New Book of Knowledge: Polk, James Knox

Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia: Polk, James K.

Encyclopedia Americana: Polk, James Knox

America the Beautiful: James Knox Polk

Spartacus Educational: James Polk

AmericanPresident.org: James Knox Polk

American Experience: James Knox Polk

New Perspectives on the West: James Knox Polk

The Californios 1821 to 1848 A time line.

The Decline of the Californios: The Case of San Diego, 1846-1856 Article by Charles Hughes, San Diego Historical Society.

San Diego's Mexican and Chicano History By Richard Griswold del Castillo and Isidro Ortiz, San Diego State University, and Rosalinda Gonzalez, Southwestern College.

Mexican Rule An essay from the Marin History Museum.

California's Untold Stories: Gold Rush! From the Oakland Museum of California.

How did Californio's get land grants after Mexico won its independence?

Where and when was the first rancho established in the Santa Barbara area? The short history of the Ortega rancho. From the Santa Barbara Independent.

From Digital History: Mexican American Voices:

Lecture Notes of Joel Michaelsen, UCSB

Exhibit of Los Rancheros Story of the ranchos in Tehama County, California. From the Tehama County Museum.

Disputed Range: Ranching a Mexican Land Grant Under U.S. Rule, 1844-1880 Chapter from the book From Rancho to Reservoir: History and Archaeology of the Los Vaqueros Watershed, California. PDF file.

The Gold Rush From PBS.

The California Gold Rush From California Environmental Resources Evaluation System.

Yahoo Directory: California Gold Rush

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict By Richard Griswold Del Castillo.

The Decline of the Californios, A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 By Leonard Pitt.

A C T I V I T Y

The Conflict Over California Land Grants

What was the fairest way to settle the conflict over California land grants?

A. Form five groups. Four groups should each argue one of the following positions on the question above.

- Automatically recognize all Mexican land grants as valid.

- Establish a Board of Land Commissioners to require all land-grant holders to prove their claims.

- Require anyone challenging the validity of a land grant to prove their case in court.

- Declare all land grants conquered territory and open them to homesteading.

B. The fifth group should act as members of Congress who will listen to the arguments of each group and question the presenters.

C. After all four groups have presented their positions, the members of Congress will meet to discuss and decide the fairest way to settle the conflict over California land grants as the other four groups observe.