CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS FOUNDATION

Bill of Right in Action

Spring 1993 (9:2)

Updated June 2001

The Executive Branch

BRIA 9:2 Home | Policing the Police | Ruling in the Name of the Emperor: How Japan Became a World Power

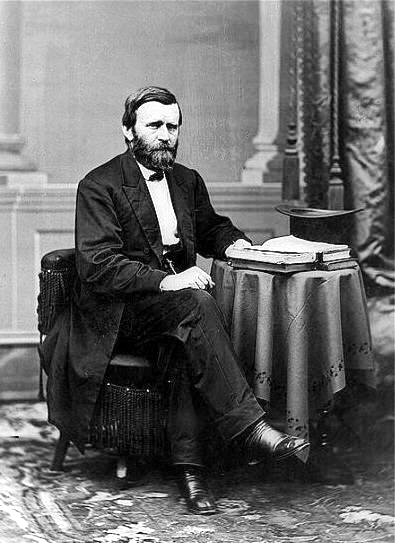

A Hero Betrayed: The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

A Hero Betrayed: The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

Some American presidents have chosen to be active leaders. They stay in touch with all the issues that affect the country. They insist on discussing ever detail of policy with their aides. Other presidents have chosen to be more relaxed. They delegate much of their power to their aides. And they only decide on the broadest outlines of new policies.

Some American presidents have chosen to be active leaders. They stay in touch with all the issues that affect the country. They insist on discussing ever detail of policy with their aides. Other presidents have chosen to be more relaxed. They delegate much of their power to their aides. And they only decide on the broadest outlines of new policies.

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, from 1869 to 1877, is a perfect illustration of what can go wrong in the executive branch if a president hands over too much power to his aides. Grant was the hero of the Civil War, and he wanted to be the hero of the peace— binding up the country's wounds. Unfortunately, he was a hero who was betrayed by the corruption of his own aides.

A Modest Beginning

In accepting the Republican Party nomination for president in 1868, Ulysses S. Grant declared, "Let there be peace." The four-year presidency of Andrew Johnson, after Lincoln's assassination, had been bitter and full of debate. Some opposed Johnson's lenient treatment of the South, and some opposed his actions in removing his secretary of war from the cabinet. He came within one vote of being removed from office by impeachment and conviction. Grant hoped to have a more peaceful presidency.

Grant's first big test came shortly after the inauguration. Wall Street dealers James Fisk and Jay Gould tried to corner the gold market. Grant's brother-in-law, Abel Corbin, persuaded Fisk and Gould that he could get the president to keep the government out of the gold market. This would allow them to bid up the price of gold without interference. Corbin even told the two Wall Street dealers that his sister, Mrs. Grant, wanted a piece of the action. These were all lies and Corbin couldn't deliver on any of his promises.

As soon as Grant saw what was happening, he ordered the sale of $4 million in government gold. This caused a price collapse and nearly ruined Fisk and Gould. Grant's quick action stopped the crisis. However, his brother-in-law's greed gave a hint of worse scandals to come.

In his first term, Grant and his appointees built a modest record of success. His secretary of the treasury, George Boutwell, reduced the huge national debt left by the Civil War. All the former Confederate states were re-admitted to the Union to try to make peace with the rebels. At the same time, Grant took some steps to stop terrorism against the freed slaves. In many Southern states, blacks and poor whites now sat in legislatures and had real power for the first time. The Southern plantation owners and many of their allies in the towns hated this fact. They encouraged the growth of the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize blacks and stop them from voting. Grant signed an Anti-Klan act that allowed him to send federal troops to the South to fight the Klan.

Grant also appeared to want to reform the civil service. Since Andrew Jackson in 1829, every president had followed the "spoils system" in making appointments. This name was based on the old saying, "to the victor belong the spoils," which means the winner should take everything. Upon taking office, every new president would kick out everyone in government service and appoint his friends, contributors, and relatives to every post.

In his 1870 annual message to Congress, Grant called for a system of examinations to select civil service appointments. "The present system," Grant said, "does not secure the best men and often not even fit men for public office. . . ." However, when his own Civil Service Commission made its report recommending a system of examinations, Grant ignored the report and continued to hand out positions to friends and allies.

In the next election in 1872, Republican reformers split away from their party to pick Horace Greeley for president. Greeley was the founder of the influential New York Tribune. He argued strongly for civil service reform, and he called for an amnesty for all former Confederates. The Democrats were so weak at this time that they, too, nominated Greeley as their presidential candidate. Grant was still so popular as a war hero that he buried Greeley in a landslide.

The Second Term: Scandals and Betrayal

Even before Grant was sworn in for his second term in 1873, Republican members of Congress were caught up in a bribery scandal. The Union Pacific Railroad had paid huge bribes to congressmen to get them to give federal money and land to the railroads. Although the bribery took place before Grant's presidency, the news began to come out during his second inauguration. It cast a dark cloud over his presidency.

Then, just as the country was sinking into an economic depression in 1873, Grant signed a bill to increase the pay of top government officials, including himself. The press called this a salary grab and attacked him. The press dug up other scandals, too, and many voters began to turn against the Republicans.

In the middle of Grant's second term, the Democrats won a majority of seats in the House of Representatives, and they pressed for many new congressional investigations. Grant's secretary of the treasury, W. A. Richardson, had to resign because of a fraud involving kickbacks from delinquent taxpayers.

The greatest scandal, and the one that came closest to Grant himself, was a plot that came to be called the Whiskey Ring. In Grant's first term, he had appointed John A. McDonald, an old Army friend, as internal revenue supervisor—or tax collector -- for the St. Louis area. McDonald worked out a scheme to let whiskey distillers cheat the government in return for "political contributions" and bribes. The distillers ended up paying taxes on only a third of the spirits they produced, cheating the U. S. Treasury out of a million dollars a year. Some of the money went to the Republican Party, and some went straight into McDonald's pocket. To keep the scheme going, many government officials were bribed, including the chief clerk of the Treasury Department. The Whiskey Ring paid him a regular salary for keeping his mouth shut.

The treasury secretary at the time, Benjamin H. Bristow, did not suspect what was going on in his own department. In the summer of 1875, he launched a series of raids on whiskey distilleries that he was certain were cheating on their taxes. Bristow was baffled when the distillers always had their records in good order when his treasury agents arrived. He had no idea that someone inside his office was warning them.

McDonald came up frequently from St. Louis to visit the White House. Grant didn't suspect his old friend and even accepted expensive gifts from him. Bristow knew that something was wrong in St. Louis. He tried to transfer McDonald to another district, but McDonald persuaded Grant to stop the move. Grant was not really part of the Whisky Ring, but McDonald bragged to his friends back in St. Louis that the president was helping their illegal scheme.

Finally, in June 1875, a federal grand jury in Missouri indicted McDonald and more than 350 distillers and government officials. The indictment named Grant's personal White House secretary, Orville Babcock. He was accused of accepting bribes from the Whiskey Ring to keep them informed about planned raids. When he heard this, Grant declared, "If Babcock is guilty, there is no man who wants him so proven guilty as I do, for it is the greatest piece of traitorism to me that a man could possibly practice."

Babcock's lawyers did everything they could to get him off. They even had witnesses lie to keep damaging evidence away from the jury. Grant himself offered a statement of his secretary's good character. In the end, Babcock was acquitted. But he was too controversial to return to the White House. After a private meeting with Grant, Babcock left Washington.

When the Whiskey Ring trials were over, John McDonald and two others went to prison. Sixty others paid large fines. The real victim of the scandal was Ulysses S. Grant. Many people began to see him as a president surrounded by corruption.

Only a few days after the Babcock trial, Grant's secretary of war, William W. Belknap (), was accused of bribery. Belknap avoided impeachment by resigning and leaving Washington. There were also scandals involving bribes to the board of public works in Washington. Many Grant appointees were caught up in these.

Final Betrayal

Grant made a sad exit from his troubled presidency in 1876. "Failures have been errors of judgment, not intent," he said in his last message to Congress. He tried to come back in 1880 and win the Republican nomination for president again. He lost to James A. Garfield. The hero of Vicksburg and Appomattox had become too associated with an era of greed and corruption that came to be called the "Gilded Age."

Grant was never a wealthy man. He gave up his military pension to become president. In the 1880s, one of Grant's sons persuaded him to invest all of his savings in a banking plan that turned out to be a fraud. Grant lost everything and faced poverty. This was the final betrayal.

Fortunately, Congress approved a special pension that allowed Grant to live out his days in dignity writing his war memoirs. His book became a well-respected history of the Civil War.

For Discussion and Writing

1. Do you think Grant was responsible for the scandals and corruption that stained his presidency? Why or why not?

2. How would you describe President Grant's style of governing? Could this have had anything to do with his misfortunes? Explain.

3. Which presidents do you think have been hands-on presidents? Which have been hands-off presidents?

4. Most historians have ranked Ulysses S. Grant as one of the nation's worst presidents. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

For Further Information

Ulysses S. Grant Chronology: A detailed chronology of the life of Ulysses S. Grant.

A C T I V I T Y

Scandal!

Form small discussion groups and rank the following types of government scandals from most serious (5) to least serious (1). Be prepared to explain your choices.

A male member of the president's cabinet is guilty of sexually harassing his female subordinates.

A close White House advisor accepts gifts from companies being investigated by the government.

Whiskey distillers bribe officials in the Treasury Department to avoid paying taxes on all the spirits they produce.

The head of the CIA lies to Congress.

A military officer working in the White House shreds documents that might incriminate members of the president's administration.