In the mid-1500s, European mariners started bringing black Africans to America as slaves. This forced migration was unique in American history.

But the slave trade was not new to Europe or Africa. In the eighth century, Moorish merchants traded humans as merchandise throughout the Mediterranean. In addition, many West African peoples kept slaves. West African slaves were usually prisoners of war, criminals, or the lowest-ranked members of caste systems.

|

|

|

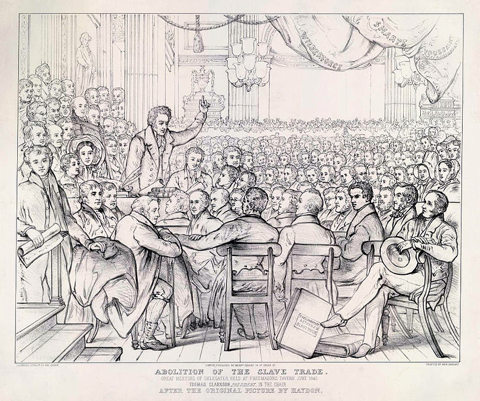

An engraving depicting the 1840 convention of the Anti-Slavery Society, held in London. People attended from around the world, including from the U.S. (Wikimedia Commons) |

The capture and sale of Africans for the American slave markets were barbaric and often lethal. Two out of five West African captives died on the march to the Atlantic seacoast where they were sold to European slavers. On board the slave vessels, they were chained below decks in coffin-sized racks. An estimated one-third of these unfortunate individuals died at sea.

In America, they were sold at auction to owners, who wanted them primarily as plantation workers. Slave owners could punish slaves harshly. They could break up families by selling off family members.

Despite the hardships, slaves managed to develop a strong cultural identity. On plantations, all adults looked after all children. Although they risked separation, slaves frequently married and maintained strong family ties. Introduced to Christianity, they developed their own forms of worship.

Spirituals, the music of worship, expressed both slave endurance and religious belief. Slaves frequently altered the lyrics of spirituals to carry the hope of freedom or to celebrate resistance.

In time, African culture enriched much of American music, theater, and dance. African rhythms found their way into Christian hymns and European marches. The banjo evolved from an African stringed instrument. The sound of the blues is nothing more than a combination of African and European musical scales. Vaudeville was partially an extension of song-and-dance forms first performed by black street artists.

Abolition and Civil War

In the 17th and 18th centuries, some blacks gained their freedom, acquired property, and gained access to American society. Many moved to the North, where slavery, although still legal, was less of a presence. African Americans, both slave and free also made significant contributions to the economy and infrastructure working on roads, canals, and construction of cities.

By the early 1800s, many whites and free blacks in Northern states began to call for the abolition of slavery. Frederick Douglass, a young black laborer, was taught to read by his master’s wife in Baltimore. In 1838, Douglass escaped to Massachusetts, where he became a powerful writer, editor, and lecturer for the growing abolitionist movement.

Frederick Douglass knew that slavery was not the South’s burden to bear alone. The economy of the industrial North depended on the slave-based agriculture of the South. Douglass challenged his Northern audience to take up the cause against Southern slavery. “Are the great principles of political freedom and natural justice, embodied in the Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” he asked. “What to the American slave is your Fourth of July?”

When the Civil War began, many Northern blacks volunteered to fight for the Union. Some people expressed surprise at how fiercely black troops fought. But black soldiers were fighting for more than restoring the Union. They were fighting to liberate their people.

Reconstruction and Reaction

With the defeat of the Confederacy, Northern troops remained in the South to ensure the slaves newly won freedom. Blacks started their own churches and schools, purchased land, and voted themselves into office. By 1870, African Americans had sent 22 representatives to Congress.

|

|

Marcus Garvey, a proponent of racial separation. (Wikimedia Commons) |

But many Southerners soon reacted to black emancipation. Supported by the surviving white power structure, Ku Klux Klan members organized terrorist raids and lynchings. They burned homes, schools, and churches.

When Northern troops left in 1877, the white power structure returned. Within a couple of decades, this power structure succeeded in completely suppressing blacks. African Americans were excluded from voting. Southern states wrote Jim Crow laws that segregated blacks from white society. Blacks lived under constant threat of violence.

The Great Migration North

Beginning in the 1890s, many blacks started moving North. World War I opened many factory jobs. In the 1920s, strict new laws drastically cut European immigration. The drop in immigration created a demand for industrial workers in the Northern cities. Southern blacks, still oppressed by segregation, began to migrate northward in increasing numbers. Young black men eagerly took unskilled jobs in meat packing plants, steel mills, and on auto assembly lines in Chicago, Omaha, and Detroit.

Black workers unquestionably improved their lives in Northern cities. Indoor plumbing, gas heat, and nearby schools awaited many arrivals from the rural South. Discrimination also met them.

Yet black urban culture blossomed. Musicians like Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver brought their music north from New Orleans. In the sophisticated urban atmosphere of Chicago, these jazz pioneers took advantage of improvements in musical instruments and new recording technologies to become celebrities in the Roaring ‘20s, also known as the Jazz Age.

Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant, preached black pride, racial separation, and a return to Africa. By the early 1920s, Garvey had an estimated 2 million followers, most of them Northern city-dwellers.

Harlem, an uptown New York City neighborhood, drew black migrants from the South. Black commerce and culture thrived in Harlem. After World War I, a group of black writers, artists, and intellectuals gathered there. Like Marcus Garvey, many sought cultural identity in their African origins. Unlike Garvey, however, they had no desire to return to Africa. They found creative energy in the struggle to be blacks and Americans.

This gathering of black artists and philosophers was called the Harlem Renaissance. Langston Hughes, a black novelist and poet, used the language of the ghetto and the rhythms of jazz to describe the African-American experience. Jazz continued its development as a uniquely American art form in Harlem, where prominent nightclubs like the Cotton Club featured great jazz composers like Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson. Their music lured whites uptown to Harlem to share the excitement of the Jazz Age. Zora Neale Hurston combined her writing ability with her study of anthropology to transform oral histories and rural black folk tales into exciting stories.

|

|

|

Jazz great Louis Armstrong. (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Depression brought many blacks and whites together for the first time. In the cities, a half-million African Americans joined predominantly white labor unions. In the South, poor black and white farmers joined together in farmers’ unions.

In 1941, African-American author Richard Wright wrote, “We black folk, our history and our present being, are a mirror of all the manifold experiences of America. What we want, what we represent, what we endure is what America is.... The differences between black folk and white folk are not blood or color, and the ties that bind us are deeper than those that separate us. The common road of hope which we all traveled has brought us into a stronger kinship than any words, laws, or legal claims.”

Today, black Americans make significant contributions to every segment of American society — business, arts and entertainment, science, literature, and politics and law. Though issues of discrimination remain, African Americans endure, achieve, and lead.

For Discussion and Writing

- Describe some of the struggles that African Americans have faced in America.

- Name some African cultural influences that have been absorbed into American society. Which do you think are most important? Why?

For Further Reading

Ash, Stephen V. The Black Experience in the Civil War South (Reflections on the Civil War Era). Santa Barbara: Praeger. 2010.

Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. New York: Random House. 2005.