|

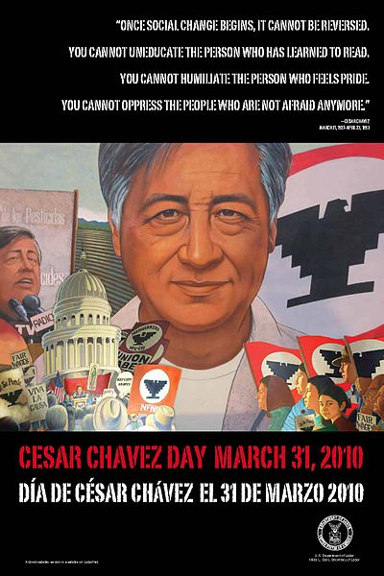

A poster for Cesar Chavez Day, March 31, an official holiday in California and Texas. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Chicano activist Cesar Chavez was one of America’s best known labor leaders. Born in Arizona in 1927, Chavez was one of six children. His family moved in California during the Great Depression, and everyone worked as farm workers, traveling from farm to farm throughout California, cultivating and harvesting crops.

In 1948, Chavez married another farm worker and began a family. By the end of the 1950s, Chavez and his wife had eight children.

He continued as a farm worker, but decided to try to organize the workers into a union to get better conditions and wages. Neither California nor federal labor laws protected farm workers. Farm workers’ mobility, their temporary employment, and their desperate economic circumstances made migrant workers difficult to organize.

In 1965, grape pickers earned an average of 90 cents an hour. Many workers, including children, labored long hours, risked injury from unsafe machinery, and suffered abusive treatment from supervisors and employers. They also endured substandard housing that lacked indoor plumbing, cooking facilities, or personal privacy.

One organization responding to farm workers’ problems was the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), founded by Dolores Huerta, who had a long record of labor activism and commitment to human rights.

In 1962, Chavez invited Huerta to work with him in creating a new farm workers’ union. According to Huerta, “Cesar ... knew that it wasn’t going to work unless people owned the union ... [and] that the only way ... [was] to organize the union ourselves.” Traveling throughout California, Chavez tirelessly met with farm workers any place he could find them — in the fields, at their homes, and in the migrant camps. His mission was to persuade them that forming a union would improve their lives.

In 1965, strikes by Filipino workers against major grape growers broke out in California’s Central Valley. “All I knew was, they [the Filipinos] wanted to strike....” Chavez explained. “We couldn’t work while others were striking.” Chavez’s union, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), joined the strike in solidarity with the Filipino workers.

Six months later, the grape strike had grown, generating national press coverage. Thousands of striking farm workers formed picket lines around the vast vineyards near Delano, California. Many growers responded fiercely, employing strikebreakers and occasionally using violence against the picketers. Despite Chavez’s call for non-violence, some strikers resorted to violence as well. Local police often harassed the union, arresting strikers on questionable charges often dismissed in court.

Inspired by the tactics and outcome of the Montgomery bus boycott, Chavez announced a consumers’ boycott of non-union grapes. The grape boycott became the core of the farm workers’ non-violent strategy. The grape strikers sustained their boycott by linking it to the larger civil rights movement, which many Americans supported.

Chicano leaders organized marches and rallies in support of the farm workers’ cause. The farm workers found allies among other unions, church groups, students, consumers, and civil rights organizations that publicized the grape boycott nationwide. Millions of consumers stopped buying grapes, creating substantial economic pressure on the large grape growers.

By 1966, some large growers conceded, recognizing the new farm workers’ union. On August 22, 1966, the AWOC and the NWFA merged to form the United Farm Workers (UFW). The new union became the largest, most influential organization in the Chicano struggle for equality and social justice.

Many growers stubbornly refused to recognize the right of the UFW to unionize their farms. The boycott and strike continued for five years. Chavez, following the example of India’s non-violent leader Mahatma Gandhi, added personal hunger strikes to the UFW’s arsenal of protest strategies. Repeated fasts, often lasting for several weeks, damaged Chavez’ health, contributing to his death in 1993. But Chavez’s fasts also generated great respect for his commitment to non-violent social change. By 1970, two-thirds of all grapes grown in the Central Valley came from unionized workers. In 1975, Chavez’s efforts helped pass the nation’s first farm labor act in California. It legalized collective bargaining and banned owners from firing striking workers.

For Further Reading

Levy, Jacqueline M. & Fred Ross Jr. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. 2007.