|

|

|

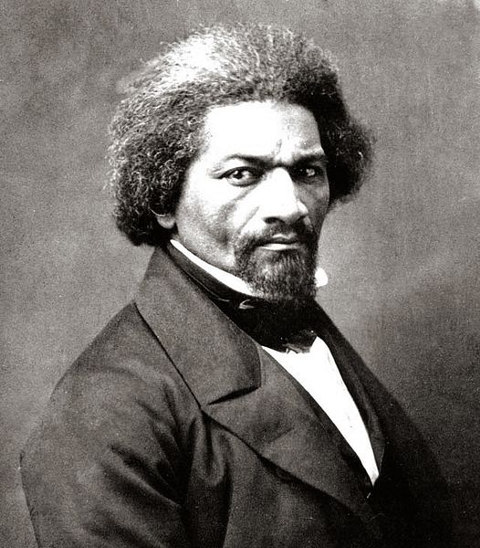

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818–1895). (Wikimedia Commons) |

The life of Frederick Douglass, the great African-American statesman, encompassed the most momentous years of his people’s long history in America. He had been born a slave about 1817 in the slave state of Maryland during the presidency of slave owner James Monroe. As he grew to manhood, the South’s “peculiar institution” was flourishing and slave owners were beginning to be possessed of a new confidence about the future of a culture based on slavery. When Frederick Douglass died in 1895, slavery had been extinct for 30 years, but his people were still not free, despite the promises of the Civil War amendments — the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution.

Given the name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, he started calling himself Douglass to throw off slave hunters after he escaped from bondage. The fugitive slave’s first public appearance came in 1841 when he rose to address an audience in Massachusetts. The effect was electrifying. Douglass presented the striking figure of a tall, handsome man possessed of a fine speaking voice, a leonine head, and lion’s fierce determination to match. Frederick Douglass told the story of his own life in slavery, the brutal treatment he had suffered, his struggle to teach himself to read, his longings for freedom and his two escapes, the second a successful one. The turning point of Douglass’ personal history probably came the day he fought back against an overseer bent on whipping him, forcing the man to back off. He learned that resistance was possible, even in slavery. Douglass’ account impressed all who heard it, and he soon became a paid employee of the Anti-Slavery Society.

When the Civil War came, Douglass rejoiced that the “slave holders themselves have saved our cause from ruin.” He was always a step or two ahead of his time and said from the beginning what many Americans were still unwilling to admit — that slavery was the root cause of the great American conflict. He was contemptuous of Abraham Lincoln’s attempts to conciliate the South during the early months of his presidency. Douglass greeted the Emancipation Proclamation, however, as a sign that the war was “no longer a mere strife for territory or dominion, but a contest of civilization against barbarism.”

He had from the start urged that blacks be enlisted as Union soldiers, recognizing not only that such action could hasten Northern victory, but also that it would be more difficult to deny the rights of citizenship to men who had worn the uniform of the United States. Although Northern leaders were at first reluctant, it was not long before black regiments were being fielded. About 180,000 African-American men eventually saw service, representing a significant part of the total Union enlistment. Douglass helped recruit some the regiments and he argued against discrimination in pay and duties, and urged retaliation against Confederate murder and enslavement of black prisoners of war.

A few weeks before his death in 1895, Douglass was asked what advice he would give to a young black American. “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!” the old man answered.

For Further Reading

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. New York: Simon & Brown. 2011.