|

|

|

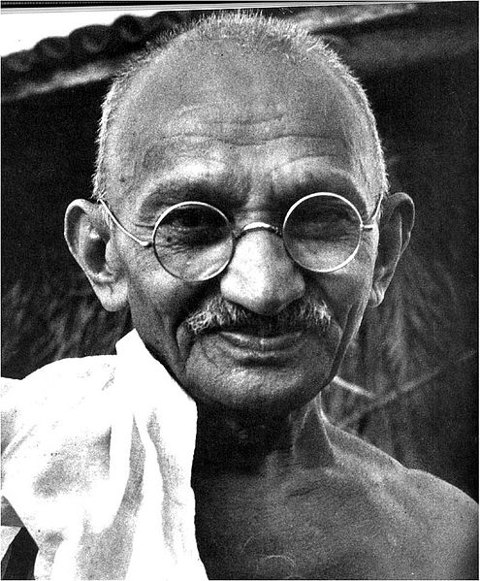

Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869–1947). (Wikimedia Commons) |

Mohandas K. Gandhi, often referred to as Mahatma, the Great Soul, was born into a Hindu merchant family in 1869. He was heavily influenced by the Hinduism and Jainism of his devoutly religious mother. She impressed on him beliefs in non-violence, vegetarianism, fasting for purification, and respect for all religions.

In 1888, Gandhi sailed to England and studied to become a lawyer. His first job for an Indian company required that he move to South Africa. The ruling white Boers (descendants of Dutch settlers) discriminated against all people of color. When railroad officials made Gandhi sit in a third-class coach even though he had purchased a first-class ticket, Gandhi refused and police forced him off the train.

This event changed his life. Gandhi became an outspoken critic of South Africa’s discrimination policies. When the Boer legislature passed a law requiring that all Indians register with the police and be fingerprinted, Gandhi, along with many other Indians, refused to obey the law. He was arrested and put in jail, the first of many times he would be imprisoned for disobeying what he believed to be unjust laws.

While in jail, Gandhi read the essay “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau, a 19th-century American writer. Gandhi adopted the term “civil disobedience” to describe his strategy of non-violently refusing to cooperate with injustice, but he preferred the Sanskrit word satyagraha (devotion to truth). Following his release, he continued to protest the registration law by supporting labor strikes and organizing a massive non-violent march. Finally, the Boer government agreed to end the most objectionable parts of the registration law.

After 20 years in South Africa, Gandhi went home to India in 1914. When Gandhi returned, he was already a hero. Gandhi devoted the rest of his life struggling against what he considered three great evils afflicting India. One was British rule, which Gandhi believed impoverished the Indian people. The second evil was Hindu-Muslim disunity caused by years of religious hatred. The last evil was the Hindu tradition of classifying millions of Indians as a caste of “untouchables.” Untouchables, those Indians born into the lowest social class, faced severe discrimination.

Gandhi expected Britain to grant India independence after World War I. When it did not happen, Gandhi called for strikes and other acts of peaceful civil disobedience. The British sometimes struck back with violence, but Gandhi insisted Indians remain non-violent. Many answered Gandhi’s call. But as the movement spread, Indians started rioting in some places. Gandhi called for order and canceled protests. He drew heavy criticism from fellow nationalists, but Gandhi would only lead a non-violent movement.

Gandhi was jailed many times. At one trial he said, “In my humble opinion, non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good.” When he was released, he continued leading non-violent protests.

When India finally gained independence, the problem became how Hindus and Muslims would share power. Distrust spilled over into violence. Gandhi spoke out for peace and forgiveness. He opposed dividing the country into Hindu and Muslim nations, believing in one unified India. In May 1947, British, Hindu, and Muslim political leaders, but not Gandhi, reached an agreement for independence that created a Hindu-dominated India and a Muslim Pakistan. As Independence Day (August 15, 1947) approached, an explosion of Hindu and Muslim looting, rape, and murder erupted throughout the land. Millions of Hindus and Muslims fled their homes, crossing the borders into India or Pakistan.

Gandhi announced that he would fast until “a reunion of hearts of all communities” had been achieved. An old man, he weakened rapidly, but he did not break his fast until Hindu and Muslim leaders came to him pledging peace. Days later, an assassin shot and killed Gandhi. The assassin was a Hindu who believed Gandhi had sold out to the Muslims.

Gandhi and others like Martin Luther King Jr. confronted injustice with non-violent methods. “It is the acid test of non-violence,” Gandhi once said, “that in a non-violent conflict there is no rancor left behind and, in the end, the enemies are converted into friends.”

For Further Reading

Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (Mahatma). Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Massachusetts: Beacon Press. 1957.