|

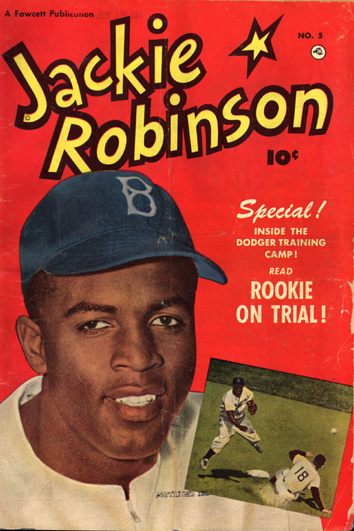

| Front cover of Jackie Robinson comic book (issue #5). Shows Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn Dodgers cap; inset image shows Jackie Robinson covering a slide at second base. (Wikimedia Commons) |

When the Dodgers decided to break the color barrier in the major leagues, they sent out scouts looking for the player who could do it. He would have to be tough, intelligent, and a great athlete. They found the right person in Jackie Robinson. Tough, Robinson played baseball as if it were war. Intelligent, Robinson attended college, rare among baseball players at that time. An incredible athlete, Robinson is the only person in U.C.L.A. sports history to letter (and star) in four sports-football, basketball, baseball, and track.

Jack Roosevelt Robinson, the youngest of five children, was born in Georgia in 1919. His father left the family when Robinson was only one year old, so his mother moved the children from Georgia to Pasadena, Calif., where Robinson was raised. He attended John Muir High School and went on to Pasadena City College and UCLA.

Robinson battled discrimination throughout his life. Growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood, he had to prove himself constantly. After college, he entered the still-segregated Army during World War II. Stationed in the South, Robinson was arrested for refusing to go to the back of a bus. After the war, he decided to play baseball professionally. Since black players could not play in the major leagues, Robinson started his baseball career in the Negro leagues, playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. He was 26 years old at the time. His biggest battle was yet to come.

In 41 games with the Monarchs, he batted .345, with 10 doubles, four triples, and five home runs. His performance was so impressive that he caught the eye of a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, was looking for a talented black player like Robinson. Rickey realized that an incredible pool of talent and skill was being wasted by not allowing blacks to play in the majors. He had decided it was time for baseball to change.

The Dodgers knew that they were taking a huge risk. They could anger their fans, other teams, and even their own players. The player they chose would have to withstand abuse and discrimination and still become a star. He would have to withstand the pressure of knowing that if he failed, it would be a long time before any black played in the majors again. Rickey believed that Robinson was the right person for the job.

In 1946, the Dodgers started Robinson out in Montreal, Canada, with their top minor-league team. Immediately accepted by his teammates and the fans in Montreal, he led the team to first place in its league. Montreal then played Louisville, Ken., for the minor league championship, the Little World Series. Jeered and booed in Louisville, Robinson did not play well in the first games. But then the teams went to Montreal. Angered at Robinson’s treatment in Louisville, the Montreal fans jeered and booed the Louisville players mercilessly. Robinson shone in the final games, and Montreal won the series. Long after the final out, fans stayed in their seats cheering, “We want Robinson! We want Robinson!”

With his success at Montreal, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the majors for the 1947 season. Rickey and Robinson agreed that Robinson would not respond to any insults, threats, or taunts. He would fight with his baseball skills alone.

As soon as the Dodgers announced that Robinson would play, the trouble began. Newspaper editorials debated whether Robinson was suitable to play in the majors. Some of his Southern teammates circulated a petition against Robinson playing. (Most of the team refused to sign it.) Outfielder Dixie Walker, a Southerner, asked to be traded. (He got his wish at the end of the season.) The Philadelphia Phillies threatened to boycott a game if Robinson played, but after the baseball commissioner threatened to ban the players from baseball, the boycott evaporated. People wrote him letters threatening his life as well as the lives of his wife and son, Jackie Jr.

At games, fans at visiting ballparks screamed insults. Players tried to spike him when he slid into bases. Once in Chicago, when sliding head first into second base, the Cubs’ shortstop kicked Robinson in the head. Pitchers tried to bean him at the plate.

On the road, some cities would not allow Robinson to stay at the team’s hotel. Often, restaurants would refuse to serve him, and he would have to eat his meals on the bus while his teammates ate inside.

Robinson did receive some support. Brooklyn fans backed him. Many blacks attended games throughout the league to cheer him on. Within a month, he had won over all his teammates, including the Southerners. When fans or opposing players became particularly hostile, team leader. Pee Wee Reese would make a point of putting his arm around Robinson to show the team’s solidarity. And many people of all races applauded Robinson’s courage.

But most of all, Robinson succeeded because of how well he played. A threat to steal whenever on base, Robinson would unnerve pitchers. He led the league in stolen bases, scored 125 runs, and batted .297. His play helped the Dodgers win the National League pennant that year, and Robinson was voted Rookie of the Year.

Robinson had remained silent the entire year. He had not answered any insults; he had not responded to any provocation; he had not spoken out against racism. He remained silent for another year. But in 1949, Robinson and Rickey agreed it was time for Robinson to speak his mind. When he did, his statements angered many players, owners, and fans throughout baseball. But their anger did not affect his play: He batted .347 and was voted the National League’s Most Valuable Player that year. Robinson continued to speak out against racism throughout his life.

When he retired from baseball in 1956, his lifetime batting average was .311, and he had stolen home 20 times in his career. In 1962, he was voted into the Hall of Fame. Although his play on the field never showed it, the pressure he endured took its toll. Plagued with diabetes, blindness in one eye, high blood pressure, and heart trouble, Robinson died on Oct. 24, 1972, at the age of 53.

The full impact he made on baseball and desegregation in this country can never be fully determined. His place in baseball’s record books goes well beyond his statistics. His life and career helped change the nation’s way of thinking. He opened the door for hundreds of great black athletes. But he probably achieved more.

In 1948, President Truman ordered the armed forces to desegregate. In 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education outlawed “separate but equal” schools. The Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s fought against segregation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened public facilities to all races. But the movement against segregation after World War II really began in 1947 with Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in baseball.

For Further Information

Please watch the film “The Jackie Robinson Story,” made in 1950, it even stars Robinson. It is an interesting social history of the time.