O Lord, O my Lord!

O my great Lord keep me from sinking down.

— From a slave song

No issue has more scarred our country nor had more long-term effects than slavery. When we celebrate American freedom, we must also be mindful of the long and painful struggle to share in those freedoms that faced and continue to face generations of African Americans. To understand the present, we must look to the past.

|

|

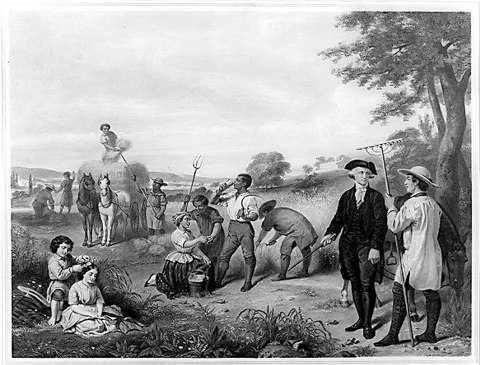

A painting depicts George Washington and workers on his plantation. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Buying and Selling Slaves

Before the Civil War, nearly 4 million black slaves toiled in the American South. Modem scholars have assembled a great deal of evidence showing that few slaves accepted their lack of freedom or enjoyed life on the plantation. As one ex-slave put it, “No day dawns for the slave, nor is it looked for. It is all night — night forever.” For many, the long night of slavery only ended in death.

In 1841, a bounty hunter kidnapped Solomon Northup, a free black man from Saratoga, New York, on the pretext that he was a runaway slave from Georgia. When the bounty hunter sold him into slavery, Northup lost his family, his home, his freedom, and even his name.

Solomon Northup was taken to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he was put into a “slave pen” with other men, women, and children waiting to be sold. In “Twelve Years a Slave,” a narrative that Northup wrote after he regained his freedom, the citizen of New York described what it was like to be treated as human property:

Freeman [the while slave broker] would make us hold up our heads, walk briskly back and forth, while customers would feel of our heads and arms and bodies, turn us about, ask us what we could do, make us open our mouths and show our teeth.... Sometimes a man or woman was taken back lo the small house in the yard, stripped, and inspected more minutely. Scars upon a slave’s back were considered evidence of a rebellious or unruly spirit, and hurt his sale.

By law, slaves were the personal property of their owners in all Southern states except Louisiana. The slave master held absolute authority over his human property as the Louisiana law made clear: “The master may sell him, dispose of his person, his industry, and his labor; [the slave] can do nothing, possess nothing, nor acquire anything but what must belong to his master.”

Slaves had no constitutional rights; they could not testify in court against a white person; they could not leave the plantation without permission. Slaves often found themselves rented out, used as prizes in lotteries, or as wagers in card games and horse races.

Separation from family and friends was probably the greatest fear a black person in slavery faced. When a master died, his slaves were often sold for the benefit of his heirs. Solomon Northup himself witnessed a sorrowful separation in the New Orleans slave pen when a slave buyer purchased a mother, but not her little girl:

The child, sensible of some impending danger, instinctively fastened her hands around her mother’s neck, and nestled her little head upon her bosom. Freeman [the slave broker] sternly ordered [the mother] to be quiet, but she did not heed him. He caught her by the arm and pulled her rudely, but she clung closer to the child. Then with a volley of great oaths he struck her such a heartless blow, that she staggered backward, and was like to fall. Oh! How piteously then did she beseech and beg and pray that they not be separated.

Perhaps out of pity, the buyer did offer to purchase the little girl. But the slave broker refused, saying there would be “piles of money to be made of her” when she got older.

Slave Labor

Of all the crops grown in the South before the Civil War including sugar, rice, and corn, cotton was the chief money-maker. Millions of acres had been turned to cotton production following the invention of the cotton gin in 1793. As more and more cotton lands came under cultivation, especially in Mississippi and Texas, the demand for slaves boomed. By 1860, a mature male slave would cost between $1,000 and $2,000. A mature female would sell for a few hundred dollars less.

Slaves worked at all sorts of jobs throughout the slaveholding South, but the majority were field hands on relatively large plantations. Men, women, and children served as field hands. The owner decided when slave children would go into the fields, usually between the ages of 10 and 12.

The cotton picking season beginning in August was a time of hard work and fear among the slaves. In his book, Solomon Northup described picking cotton on a plantation along the Red River in Louisiana:

An ordinary day’s work is two hundred pounds.... The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as if is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see.... The day’s work over in the field, the baskets are “toted,” or in other words, carried to the gin house, where the cotton is weighed. No matter how fatigued and weary he may be ... a slave never approaches the gin-house with his basket of cotton but with fear. If it falls short of weight ... he knows that he must [be whipped]. And if he has exceeded it by ten or twenty pounds, in all probability his master will measure the next day’s task accordingly.

Only when the slaves finally finished working for their master could they return to their own crude cabins to tend to their own family needs.

|

|

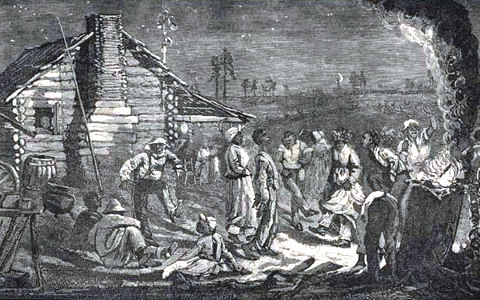

An illustration of slave’s life from a song book published in 1881. (Wikimedia Commons) |

‘The Quarters’

Slave families lived in crowded cabins called “the quarters.” Usually bare and simple, these shelters were cold in winter, hot in summer, and leaky when it rained. Slave food was adequate but monotonous, consisting mainly of corn bread, salt pork (or bacon), and molasses. The master also usually provided a winter and a summer set of clothes, often the cast-offs of white people. Sickness was common and the infant death rate doubled that of white babies.

The lives of black people under slavery in the South were controlled by a web of customs, rules, and laws known as “slave codes.” Slaves could not travel without a written pass. They were forbidden to learn how to read and write. They could be searched at any time. They could not buy or sell things without a permit. They could not own livestock. They were subject to a curfew every night.

Marriage among slaves had no legal standing and always required the approval of the master. Generally, slaves could marry others living at their plantation, or at neighboring ones. Solomon Northup discovered the following rules during his enslavement in Louisiana:

Either party can have as many husbands or wives as the owner will permit, and either is at liberty to discard the other at pleasure. The law in relation to divorce, or to bigamy, and so forth, is not applicable to property, of course. If the wife does not belong on the same plantation with the husband, the latter is permitted to visit her on Saturday nights, if the distance is not too far.

Slave Resistance

In “Twelve Years a Slave,” Northup reported one instance in which a young slave woman named Patsey was brutally whipped for visiting a neighboring plantation without permission:

The painful cries and shrieks of the tortured Patsey, mingling with the loud and angry curses of Epps [the slave master whipping her] loaded the air. She was terribly lacerated — I may say, without exaggeration, literally flayed. The lash was wet with blood....

13th Amendment (1865)Neither slavery not involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. |

How did the slaves react to the whippings, the endless labor for others’ profit, the lack of freedom? Some like Nat Turner rebelled. In 1831, he led a slave revolt that left nearly 60 white persons dead in Virginia. Such insurrections were relatively rare in the South. White people outnumbered slaves in most places, possessed firearms, and could call on the power of the government to suppress rebellions. Nevertheless, slaves everywhere found other ways to resist their bondage. They sabotaged tools and crops, pretended illness, and stole food from the master’s own kitchen. The most effective way that a slave could retaliate against an owner was to run away. It is estimated that 60,000 black people fled slavery before the Civil War.

Solomon Northup attempted to run away but failed. Then, in 1852, a white carpenter with abolitionist sentiments met Northup and learned about his kidnapping. The carpenter wrote several letters to New York state officials on behalf of Northup. In response, the governor of New York sent an agent carrying documents proving that Northup was a free black man. After a court hearing in January 1853, a Louisiana judge released Northup from his bondage. He finally returned home to his wife and children.

When Solomon Northup wrote the narrative of his experiences in 1853, he left little doubt about his feelings toward slave owners: “A day may come — it will come... — a terrible day of vengeance, when the master in his turn will cry in vain for mercy.”

For Discussion and Writing

- In 1850, a Southern slave owner might have said something like this: “Our slaves are like children who need to be cared for and disciplined. They are content and are actually better off than free white laborers working in northern factories.” How do you think Solomon Northup would have responded to these remarks?

- What was the legal status of slaves and their families?

- The 13th Amendment was finally ratified in 1865, long after most other nations in the world had abolished slavery. Why do you think slavery lasted so long in the American South?

- Today practices such as slavery seem to us unjust and unthinkable. When students of the future read about our world in their history books, will they be horrified by any of the conditions we find acceptable? What causes public opinion to change?

For Further Reading

Boles, John B. Black Southerners, 1619–1869. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1984.

Stampp, Kenneth M. The Peculiar Institution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

A C T I V I T Y

Runaway Slaves

1. In this activity and based on the reading, the class will create narratives of six slaves who have run away from different southern plantations in 1850. After forming small groups, assign each group one of the following profiles. Each should work cooperatively to write a narrative of one of the following runaway slaves:

Jackson, age 25, a field worker with many scars on his back.

Polly, age 18, a field worker who is 8 months pregnant.

Eliza, age 15, a house servant whose mother was sold to another master one year ago.

Thomas, age 12, a stable boy who wants to learn how to read and write.

Hattie, age 45, a cook whose master recently died.

Marcus, age 70, a coachman and butler who has worked for the same family all of his life.

2. The following questions are intended to help the groups develop their slave narratives. Every response should be written in first person as if the runaway slave had answered himself or herself.

a. What is your name and how old are you?

b. What was it like to be sold?

c. What was your work day like?

d. What was your family life like in the slave quarters?

e. What was it like to be punished for violating a slave code regulation?

f. What was it like to resist your master without his knowing it?

g. Why did you run away?

3. Someone in each group should now take on the role of the runaway slave and read the group’s first person narrative to the rest of the class.

4. After all the narratives have been read, hold a class discussion on what seemed to be the worst part of slavery in the American South. This could also be the subject of an essay assignment.