The modern civil rights movement grew out of a long history of social protest. In the South, any protest risked violent retaliation. Even so, between 1900 and 1950, community leaders in many Southern cities protested segregation. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the leading civil rights organization of this era, battled racism by lobbying for federal anti-lynching legislation and challenging segregation laws in court.

|

|

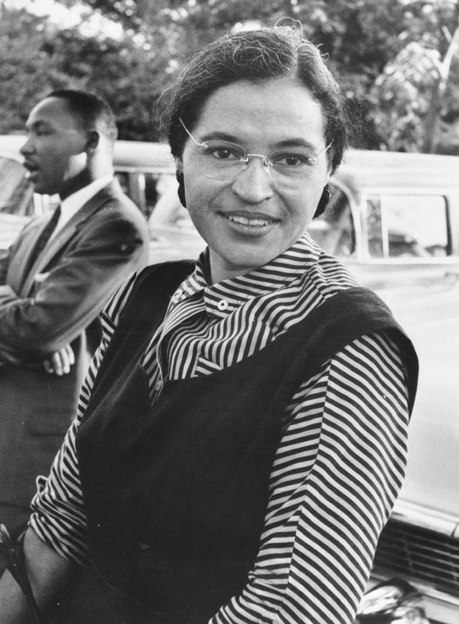

Rosa Parks’ act of defiance helped spark the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Behind Parks is the Reverent Martin Luther King Jr. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Following World War II, a great push to end segregation began. The NAACP grew from 50,000 to half a million members. The walls of segregation that existed outside the South started crumbling. In 1947, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball and soon black athletes participated in all professional sports. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the integration of the armed forces.

The greatest victory occurred in 1954. In Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional separate schools for black people and white people. This deeply shocked many Southern white people. White Citizens Councils, joined by prominent citizens, sprouted throughout the South. They vowed that integration would never take place. In this atmosphere, the social protests of the civil rights movement were born.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

In December 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, one of the first major protests began. Rosa Parks, a black woman, refused to give her bus seat to a white passenger, as required by the city’s segregation laws. Although often depicted as a weary older woman too tired to get up and move, Parks was actually a longtime, active member of the NAACP. A committed civil rights activist, she decided that she was not going to move. She was arrested and jailed for her defiant and courageous act.

The NAACP saw Parks’ arrest as an opportunity to challenge segregation laws in a major Southern city. The NAACP called on Montgomery’s black political and religious leaders to advocate a one-day boycott protesting her arrest. More than 75 percent of Montgomery’s black residents regularly used the bus system. On the day of the boycott, only eight black people rode Montgomery’s buses.

The success of the one-day boycott inspired black leaders to organize a long-term boycott. They demanded an end to segregation on the city’s buses. Until this demand was met, black people would refuse to ride Montgomery’s buses. A young Baptist minister named Martin Luther King Jr. led the boycott.

Car pools were organized to get black participants to work. Many walked where they needed to go. After a month, Montgomery’s businesses were beginning to feel the boycott’s effects. Some segregationists retaliated. black people were arrested for walking on public sidewalks. Bombs exploded in four black churches. King’s home was firebombed.

King conceived of a strategy of non-violence and civil disobedience to resist the violent opposition to the boycott. In school, Henry David Thoreau’s writings on civil disobedience had deeply impressed King. But King did not believe the Christian idea of “turning the other cheek” applied to social action until he studied the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, who introduced the “weapon” of non-violence during India’s struggle for independence from Great Britain. “We decided to raise up only with the weapon of protest,” King said. “It is one of the greatest glories of America.... Don’t let anyone pull you so low as to hate them. We must use the weapon of love.” The tactic of non-violence proved effective in hundreds of civil rights protests in the racially segregated South.

The Montgomery bus boycott lasted 382 days. It ended when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on the city’s buses was unconstitutional.

The success of the boycott propelled King to national prominence and to leadership in the civil rights movement. When some Southern black ministers established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, they chose King as its leader. The SCLC continued to lead non-violent boycotts, demonstrations, and marches protesting segregation throughout the South.

The Sit-ins

In February 1960, four black college freshmen sat down at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, and politely asked to be served. They were ignored but remained seated until the counter closed. The next day they returned with more students, who sat peacefully at the counter waiting to be served. They, like the protesters in Montgomery, were practicing non-violent, civil disobedience. The Greensboro lunch-counter demonstrations were called “sit-ins.” As word of them spread, other students in cities throughout the South started staging sit-ins. By April 1960, more than 50,000 students had joined sit-ins.

The tactic called for well-dressed and perfectly behaved students to enter a lunch counter and ask for service. They would not move until they were served. If they were arrested, other students would take their place.

Students in many cities endured taunts, arrests, and even beatings. But their persistence paid off. Many targeted businesses began to integrate.

In October 1960, black students across the nation formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC — pronounced “snick”) to carry on the work that students had begun in the Greensboro sit-ins. SNCC operated throughout the deep South, organizing demonstrations, teaching in “Freedom Schools,” and registering voters.

|

|

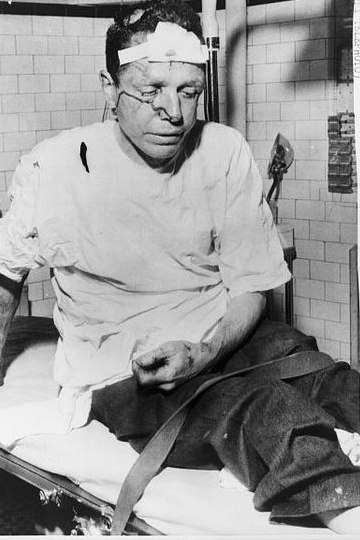

A Freedom Rider sits in an Alabama hospital after being beaten. (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Freedom Ride

Some of the most dangerous and dramatic episodes of the civil rights movement took place on the Freedom Ride. This was organized in 1961 by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights group committed to direct, non-violent action. More than a decade earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had declared segregation on interstate buses and in interstate terminals unconstitutional. Despite this decision, the buses and stations remained rigidly segregated.

In May 1961, black and white freedom riders boarded buses bound for Southern states. At each stop, they planned to enter the segregated areas. CORE Director James Farmer said: “We felt we could count on the racists of the South to create a crisis so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce the law.” At first, the riders met little resistance. But in Alabama, white supremacists surrounded one of the freedom riders’ buses, set it afire, and attacked the riders as they exited. Outside Birmingham, Alabama, a second bus was stopped. Eight white men boarded the bus and savagely beat the non-violent freedom riders with sticks and chains.

When he heard about the violence, President Kennedy sent federal agents to protect the freedom riders. Although the president urged the freedom riders to stop, they refused. Regularly met by mob violence and police brutality, hundreds of freedom riders were beaten and jailed. Although the Freedom Ride never reached its planned destination, New Orleans, it achieved its purpose. At the prodding of the Kennedy administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered the integration of all interstate bus, train, and air terminals. Signs indicating “colored” and “white” sections came down in more than 300 Southern stations.

Birmingham

In 1963, Martin Luther King announced that the SCLC would travel to Birmingham, Alabama, to integrate public and commercial facilities. In defiance of Supreme Court orders, Birmingham had closed its public parks, swimming pools, and golf courses rather than integrate them. Its restaurants and lunch counters remained segregated.

Peaceful demonstrators singing “We Shall Overcome” met an enraged white populace and an irate police chief named Eugene “Bull” Connor. Day after day, more demonstrators, including King, were thrown in jail. After a month, African-American youth, aged 6 to 18, started demonstrating. They too were jailed, and when the jails filled, they were held in school buses and vans. As demonstrations continued, Connor had no place left to house prisoners. Americans watched the evening news in horror as Connor used police dogs, billy clubs, and high-pressure fire hoses to get the children demonstrators off the streets. As tension mounted, city and business leaders gave in. They agreed to desegregate public facilities, hire black employees, and release all the people in jail.

March on Washington

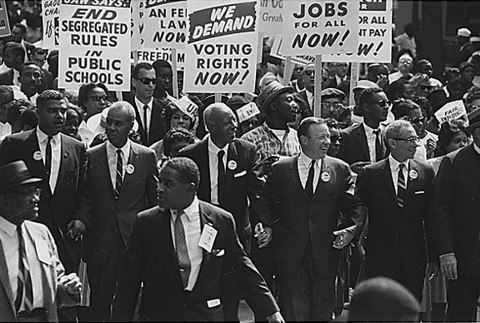

The violence in Birmingham and elsewhere in the South prompted the Kennedy administration to act. It proposed a civil rights bill outlawing segregation in public facilities and discrimination in employment. The bill faced solid opposition from Southern members of Congress. In response, civil rights leaders organized a massive march on Washington, D.C. On August, 28, 1963, hundreds of thousands of Americans traveled to the nation’s capital to demonstrate for civil rights. The peaceful march culminated in a rally where civil rights leaders demanded equal opportunity for jobs and the full implementation of constitutional rights for racial minorities. Martin Luther King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. It inspired thousands of people to increase their efforts and thousands of others to join the civil rights movement for the first time. Full press and television coverage brought the March on Washington to international attention.

Mississippi Freedom Summer

Much of the civil rights movement focused on voting rights. Since Reconstruction, Southern states had systematically denied African Americans the right to vote. Perhaps the worst example was Mississippi, the poorest state in the nation. Many Mississippi counties had no registered black voters. black people lived under the constant threat of violence. Medgar Evers, a major civil rights leader in Mississippi, was murdered outside his home in 1963.

In 1964, SNCC and other civil rights organizations turned their attention to Mississippi. They planned to register Mississippi black people to vote, organize a “Freedom Democratic Party” to challenge the white people-only Mississippi Democratic Party, establish freedom schools, and open community centers where black people could obtain legal and medical assistance.

In June, only days after arriving in Mississippi, three Freedom Summer workers disappeared. They had been arrested for speeding and then released. On August 4, their bodies were found buried on a farm. The discovery directed the media’s attention to Mississippi, just two weeks before the Democratic National Convention was scheduled to begin.

A major dispute over the Mississippi delegation was brewing. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party had elected delegates to attend the convention. They demanded to be seated in place of the segregationist Mississippi Democrats. Ultimately, a compromise was struck, but the power struggle at the convention raised the issue of voting rights before the entire nation.

Selma

In December 1964, the SCLC started a voter-registration campaign in Selma, Alabama. Although black people outnumbered white people in Selma, few were registered to vote. For almost two months, Martin Luther King led marches to the courthouse to register voters. The sheriff responded by jailing the demonstrators, including King. The SCLC got a federal court order to stop the sheriff from interfering, but election officials still refused to register any black people.

King decided to organize a march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. As marchers crossed the Edmund Pettis Bridge out of Selma, state police attacked. A national television audience watched police beat men, women, and children mercilessly. This brutal attack shocked the nation and galvanized support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which would put elections in Southern states under federal control.

Two weeks later, the march resumed under federal protection. More than 20,000 people celebrated when the marchers reached Montgomery, the site of the bus boycott 10 years earlier.

|

|

Thousands of Americans joined the March on Washington in August 1963. (Wikimedia Commons) |

The North

Civil rights demonstrations also took place in the North. Although legal segregation existed primarily in the South, Northern black people endured discrimination in employment and housing. Most lived in poverty in urban ghettos. King led demonstrations in Chicago, which the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights called the “most residentially segregated large city in the nation.” Complaints of police brutality mobilized many African Americans and their supporters. They organized street rallies, picket lines, and other forms of non-violent protest that had dominated the civil rights movement in the South. Like their counterparts in the South, many of these protesters encountered hostility among the white population.

Until the 1960s, the civil rights movement had been integrated and non-violent. As the decade continued, however, the mood of confrontation intensified, reflecting the growing frustration of millions of African Americans. Major riots broke out in American cities, including Newark, Detroit, and Los Angeles. Thousands of injuries and arrests intensified the social conflicts. The 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King sparked more violence, forcing the United States to confront its most troubling domestic crisis since the Civil War.

A “black power” movement emerged, challenging the philosophies of non-violence and integration. Like the non-violent movement, this development had powerful historical roots. It originated in the violent resistance against slavery and continued in the outlook of major black spokespersons throughout the 20th century. In the late 1960s, SNCC and CORE adopted “black power.” Activists argued that legal gains alone without corresponding economic and political power would deny millions of African Americans equal opportunity.

By the end of the decade with the Vietnam War escalating, the entire nation was in turmoil. Anti-war protests crossed paths with unrest in the cities. Black power took many forms. The Nation of Islam preached black separatism. Members of the Black Panther Party set up breakfast programs for children and published a daily newspaper while they armed themselves for a revolution. The media shifted focus from non-violent black leaders to the most radical black spokespersons. These new, more militant philosophies created considerable anxiety in mainstream America. By the mid-1970s, however, the Vietnam War had ended and the protests had subsided.

But the civil rights movement left a lasting legacy, forever changing the face of America. It pushed America toward its stated ideal of equality under the law. The civil rights movement did not end America’s racial problems, but it showed that great changes are possible.

For Discussion and Writing

- What do you think were the most effective strategies used during the civil rights movement? Why?

- During the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King stressed the involvement of many groups and reached out to people of all colors in the struggle for equality. The black power movement focused on organizing black people, sometimes to the exclusion of other groups. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each approach? Which do you think is more effective? Why?

For Further Reading

Dierenfield, Bruce J. The Civil Rights Movement. United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited. 2008.

Bullard, Sara. Free At Last: A History of the Civil Rights Movement and Those Who Died in the Struggle. New York: Oxford University Press. 1995.