Gandhi led the movement for independence in India by using non-violent civil disobedience. His tactics drove the British from India, but he failed to wipe out ancient Indian religious and caste hatreds.

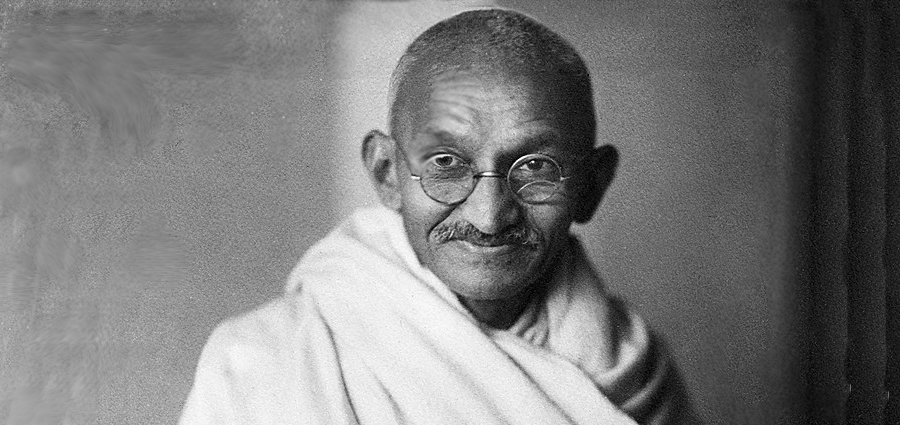

Naturally shy and retiring, Mohandas K. Gandhi was a small, frail man with a high-pitched voice. He didn’t seem like a person destined to lead millions of Indians in their battle for independence from the British Empire . And the tactics that he insisted his followers use in this struggle—non-violent civil disobedience —seemed unlikely to drive a powerful empire from India.

Gandhi was born into a Hindu merchant caste family in 1869. He was the youngest child. His father was the chief minister of an Indian province and showed great skill in maneuvering between British and Indian leaders. Growing up, Gandhi exhibited none of his father’s interest in or skill at politics. Instead, he was heavily influenced by the Hinduism and Jainism of his devoutly religious mother. She impressed on him beliefs in non-violence, vegetarianism, fasting for purification, and respect for all religions. “Religions are different roads converging upon the same point,” he once said.

In 1888, Gandhi sailed for England where, following the advice of his father, he studied to become a lawyer. When he returned to India three years later, he took a job representing an Indian ship-trading company that was involved in a complicated lawsuit in South Africa.

Traveling to South Africa in 1893, Gandhi soon discovered that the ruling white Boers, descendants of Dutch settlers, discriminated against the dark-skinned Indians who had been imported as laborers. Gandhi himself experienced this discrimination when railroad officials ordered him to sit in a third-class coach at the back of a train even though he had purchased a first-class ticket. Gandhi refused the order and police forced him off the train.

This event changed his life. Gandhi soon became an outspoken critic of South Africa’s discrimination policies. This so angered the Boer population that at one point a white mob almost lynched him.

At the turn of the century, the British fought the Boers over control of South Africa with its rich gold and diamond mines. Gandhi sympathized with the Boers, but sided with Britain because he then believed that the British Empire “;existed for the benefit of the world.” Britain won the war, but much of the governing of South Africa remained in the hands of the Boers.

In 1907, the Boer legislature passed a law requiring that all Indians register with the police and be fingerprinted. Gandhi, along with many other Indians, refused to obey this law. He was arrested and put in jail, the first of many times he would be imprisoned for disobeying what he believed to be unjust laws.

While in jail, Gandhi read the essay “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau, a 19th-century American writer. Gandhi adopted the term “civil disobedience” to describe his strategy of non-violently refusing to cooperate with injustice, but he preferred the Sanskrit word satyagraha (devotion to truth). Following his release from jail, he continued to protest the registration law by supporting labor strikes and organizing a massive non-violent march. Finally, the Boer government agreed to a compromise that ended the most objectionable parts of the registration law.

Having spent more than 20 years in South Africa, Gandhi decided that his remaining life’s work awaited him in India. As he left South Africa in 1914, the leader of the Boer government remarked, The saint has left our shores, I sincerely hope forever.”

Civil Disobedience in India

When Gandhi returned to India, he was already a hero in his native land. He had abandoned his western clothing for the simple homespun dress of the poor people. This was his way of announcing that the time had come for Indians to assert their independence from British domination. He preached to the Indian masses to spin and weave in lieu of buying British cloth.

The British had controlled India since about the time of the American Revolution. Gaining independence would be difficult, because Indians were far from united. Although most Indians were Hindus, a sizeable minority were Muslims . The relationship between the two groups was always uneasy and sometimes violent.

One of Britain’s main economic interests in India was to sell its manufactured cloth to the Indian people. As Britain flooded India with cheap cotton textiles, the village hand-spinning and weaving economy in India was crippled. Millions of Indians were thrown out of work and into poverty.

Gandhi struggled throughout his life against what he considered three great evils afflicting India. One was British rule, which Gandhi believed impoverished the Indian people by destroying their village-based cloth-making industry. The second evil was Hindu-Muslim disunity caused by years of religious hatred. The last evil was the Hindu tradition of classifying millions of Indians as a caste of “untouchables”. Untouchables, those Indians born into the lowest social class, faced severe discrimination and could only practice the lowest occupations.

In 1917, while Britain was fighting in World War I , Gandhi supported peasants protesting unfair taxes imposed by wealthy landowners in the Bihar province in northeastern India. Huge crowds followed him wherever he went. Gandhi declared that the peasants were living “under a reign of terror.” British officials ordered Gandhi to leave the province, which he refused to do. “I have disregarded the order,” he explained, “in obedience to the higher law of our being, the voice of conscience.”

The British arrested Gandhi and put him on trial. But under pressure from Gandhi’s crowds of supporters, British authorities released him and eventually abolished the unjust tax system. Gandhi later said, “I declared that the British could not order me around in my own country.”

Despite his differences with Britain, Gandhi actually supported the recruitment of Indian soldiers to help the British war effort. He believed that Britain would return the favor by granting independence to India after the war.

Gandhi Against the Empire

Instead of granting India independence after World War I, Britain continued its colonial regime and tightened restrictions on civil liberties. Gandhi responded by calling for strikes and other acts of peaceful civil disobedience. During one protest assembly held in defiance of British orders, colonial troops fired into the crowd, killing more than 350 people. A British general then carried out public floggings and a humiliating “crawling order.” This required Indians to crawl on the ground when approached by a British soldier.

The massacre and crawling order turned Gandhi against any further cooperation with the British government. In August 1920, he urged Indians to withdraw their children from British-run schools, boycott the law courts, quit their colonial government jobs, and continue to refuse to buy imported cloth. Now called “Mahatma,” meaning “Great Soul,” Gandhi spoke to large crowds throughout the country. “We in India in a moment,” he proclaimed, “realize that 100,000 Englishmen need not frighten 300 million human beings.”

Many answered Gandhi’s call. But as the movement spread, Indians started rioting in some places. Gandhi called for order and canceled the massive protest. He drew heavy criticism from fellow nationalists, but Gandhi would only lead a non-violent movement.

In 1922, the British arrested Gandhi for writing articles advocating resistance to colonial rule. He used his day in court to indict the British Empire for its exploitation and impoverishment of the Indian people. “In my humble opinion,” he declared at his trial, non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good.” The British judge sentenced him to six years in prison.

When he was released after two years, Gandhi remained determined to continue his struggle against British colonial rule. He also decided to campaign against Hindu-Muslim religious hatred and Hindu mistreatment of the so-called untouchables, whom he called the Children of God. In Gandhi’s mind, all of these evils had to be erased if India were to be free.

In 1930, Gandhi carried out his most spectacular act of civil disobedience. At that time, British colonial law made it a crime for anyone in India to possess salt not purchased from the government monopoly. In defiance of British authority, Gandhi led thousands of people on a 240-mile march to the sea where he picked up a pinch of salt. This sparked a mass movement among the people all over the country to gather and make their own salt.

Gandhi was arrested and jailed, but his followers marched to take over the government salt works. Colonial troops attacked the marchers with clubs. But true to Gandhi’s principle of non-violence, the protesters took the blows without striking back. Gandhi explained, I want world sympathy in this battle of Right against Might.

Gandhi now held the attention of the world, which pressured the British to negotiate with Indian leaders on a plan for self-rule. The British, however, stalled the process by making proposals that aggravated Indian caste and religious divisions.

The Mahatma decided that he had to do everything he could to eliminate Hindu prejudice and discrimination against the untouchables if India were ever to become a truly free nation. In 1932, he announced a fast unto death” as part of his campaign to achieve equality for this downtrodden caste. Gandhi ended his fast when some progress was made toward this goal, but he never achieved full equality for the Children of God.”

Gandhi also dreamed of a united as well as a free India. But distrust between the two factions led to increasing calls for partitioning India into separate Hindu and Muslim homelands.

Independence and Assassination

During World War II , colonial officials cracked down on a movement calling for the British to “Quit India.” They imprisoned Gandhi and many other Indians until the end of the war. Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill, declared, “I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.”

When the British people voted out Churchill’s government in 1945, Indian independence became inevitable. But the problem was how the Hindu majority and Muslim minority would share power in India. Distrust spilled over into violence between the two religious groups as the Muslims demanded a separate part of India for their own nation, which they would call Pakistan.

Disheartened by the religious hatred and violence, Gandhi spoke to both Hindus and Muslims, encouraging peace and forgiveness. He opposed dividing the country into Hindu and Muslim nations, believing in one unified India.

Finally, in May 1947, British, Muslim, and Hindu political leaders reached an agreement for independence that Gandhi did not support. The agreement created a Hindu-dominated India and a Muslim Pakistan. As Independence Day (August 15, 1947) approached, an explosion of Hindu and Muslim looting, rape, and murder erupted throughout the land. Millions of Hindus and Muslims fled their homes, crossing the borders into India or Pakistan.

Gandhi traveled to the areas of violence, trying to calm the people. In January 1948, he announced that he would fast until a reunion of hearts of all communities had been achieved. At age 78, he weakened rapidly. But he did not break his fast until Hindu and Muslim leaders came to him pledging peace.

On January 30, 1948, an assassin shot and killed the Great Soul of India while he was attending a prayer meeting. The assassin was a Hindu who believed Gandhi had sold out to the Muslims.

Sadly, the peace he had brokered between Hindus and Muslims did not last. The ancient hatreds remained. War has erupted between India and Pakistan several times, and the two countries remain hostile to one another to this day.

Who was Mahatma Gandhi? He was a physically small man with a big idea who achieved great things. He worked for the dignity of Indians in South Africa, struggled for Indian independence, and inspired others like Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States to confront injustice with non-violent methods. It is the acid test of non-violence, Gandhi once said, that in a non-violent conflict there is no rancor left behind and, in the end, the enemies are converted into friends.

For Discussion and Writing

- What non-violent methods did Gandhi use in South Africa and India to achieve his goals?

- How did Gandhi justify breaking the law in his civil disobedience campaigns? Do you agree with him? Explain.

- When, if ever, do you think non-violent civil disobedience is justified?

- Although Gandhi never used or advocated violence, he did not absolutely oppose it. I do believe that where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, he wrote, I would advise violence. Describe a situation where you think Gandhi might agree that resorting to violence was necessary.

For Further Information

Non-Violent Resistance And Social Transformation: A highly informative web site describing the importance of civil disobedience to Gandhi.

A C T I V I T Y

Non-violent Civil Disobedience

Since Gandhi, many individuals and groups have employed non-violent civil disobedience. The question has often arisen whether the civil disobedience was justified. In this activity, students examine various situations and tell whether the situation calls for civil disobedience.

- Form small groups.

- Each group should discuss each of the situations below. For each, the group should decide two issues:

- Does the situation justify non-violent civil disobedience? Explain.

- If so, what action would you recommend for those seeking to change the situation? If not, what action would you recommend? Explain.

- Call on groups to report their decisions and reasons for them.

Situations

- In 1955, the year after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered all schools desegregated, most public facilities—hotels, restrooms, water fountains, etc.—remained rigidly segregated in the South. African Americans were demanding full integration.

- In 1964 at the University of California in Berkeley, university rules banned all political or religious speakers, fund raising, or recruitment from the campus unless first approved by the campus administration. Students were demanding to exercise what they consider their First Amendment rights to speak out on issues, raise funds for causes, and recruit members of political and religious organizations.

- In 1967, America was deeply involved in the Vietnam War. Many people believed the war was wrong and demanded that the troops be brought home.

- In its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the U. S. Supreme Court in effect legalized abortion in America. Many people today believe abortion is murder and it should be stopped.